- Home

- Craig DiLouie

The Children of Red Peak Page 5

The Children of Red Peak Read online

Page 5

Part of him believed.

David could deny all he wanted, while Beth wanted to have it both ways by attributing the phenomenon to a glitch of mental perception. Barking up opposite trees, and both of them were wrong.

Deacon believed something had happened up on that monolith, something that defied rational explanation.

The Gospel of the Sad Cat would be his way of starting a dialogue.

He was due in LA in a couple of hours. The band was getting together for a rehearsal to tighten up their set before tomorrow night’s club gig. They’d have to wait, which would piss them off.

Oh well. This was art, which trumped everything. That included eating and sleeping, not to mention rehearsals.

Pen poised over blank paper, he gazed across the ashfall and breathed the poisonous atmosphere that reeked like a chimney’s sooty asshole. In the distance, the crimson glow outlined the mountains under a pall of white smoke. Since the wildfire had started, it had grown to become a breathing god, its cloud spinning clockwise like a hurricane when seen from space.

Slowly, reality collapsed around his own fresh burns. The heartbreak of seeing his childhood best friend Stepford Wifeing himself, the exquisite pain of loss when he saw Beth again, the horror of facing Emily in her casket.

And the church organ. Its droning and haunting sound being the worst of all.

Organs always reminded him of his mother.

We played so beautifully, he wrote. His ode to Beth.

The pen paused over the page before scribbling again.

We played so beautifully, but the wall fell down.

We played so beautifully, but the wall came round.

He’d write a song for each of his friends, render a few classic spirituals like “Nothing but the Blood” in moody Goth, and build toward a dirty, howling climax followed by a triumph—a vast choir of sopranos discordantly heralding the resurrection of the dead, leaving behind only bloodstains to bury.

Time blurred. His phone rang. He ignored it.

The second time, he answered it.

“I’m working.”

“So are we,” Laurie said. “Unfortunately, we seem to be missing our singer.”

“Screw your singer. I’m working.”

Silence on the line. Laurie knew what he was like when the muse burned him alive, and that he always produced his best lyrics in this state. On the other hand, she was in a band, the band had a gig, and the gig was tomorrow, and this weighed equally in her mind as she was a practical person who lived in the real world.

“All right,” she said.

“All right,” he echoed.

“Just hurry your ass up.”

“Hurrying my ass up. Right.” He terminated the call. “Shit.”

His fugue was over. Deacon inspected the pages he’d filled with black ink violent as flame. His hands were smudged with it. He had no idea what he’d written or how strong it was. When he fell into the zone, his hand caught a fever and did its own thing, like automatic writing.

Good enough. Okay. The new album screamed for birth, but he had a gig first, and in the end, the gigs trumped all. Standing in front of a crowd and ripping himself to shreds. Inviting them to share in his pain, and survive it together.

He read the last line of his hurried scrawl.

The meaning of life should transcend the meaning of death.

Amen. Deacon closed his book and roared out of the parking lot, bound for the City of Angels.

He drove down the Golden State through Los Padres until turning west along the 110. The great city’s roaring heart and clogged arteries absorbed him as just another red blood cell among ten million. The 110 brought him to the Santa Monica Freeway, an autobahn of hurtling glass and steel where speed limits flickered past as mere suggestion, and which dropped him in Crenshaw. There, Cats Are Sad rented rehearsal space in a self-storage facility for twenty-five bucks a night.

With his rural childhood followed by years living in suburban foster homes, the city had baffled Deacon when he’d first shown up with little money and no plans other than to see the world and then disappear into it. For the first few months, he learned the geography, the value of resilience, the treasures buried among the homogenized sprawl, and how the metropolis was in reality a confederation of smaller cities forming a tapestry of different cultures, ethnicities, and economies. They were the real Los Angeles, Los Angeles itself being a fantasy projected by need and want and hunger.

Odd jobs, roommates, music lessons, and open mic nights and jams got him into the music scene. Deacon would walk onstage and sing old spirituals like “Go Tell It on the Mountain” to whatever jam the ad-hoc band cooked up. Following Dr. Klein’s therapy, he’d never stopped writing poems to process the trauma he now called his muse, and he started singing them onstage as songs.

This got him into Sweet Frostbite, a neopunk band that shattered after the bassist’s messy suicide. Then the post-metal blackgaze band Night Broadcast, which came close to hitting with “Love to Hate,” and which fell apart over ego and burnout. After that, Deacon found a new home with Cats Are Sad, a Goth band that with him as frontman evolved into something new, something that might best be described as nu gaze, but with the vocals out front and a dark-brewed Goth flavor. Their songs were packed with grunge lyrics dedicated to classic themes of alienation, low self-esteem, trauma, and the raw want of being young.

During these years, he lived with bandmates. Anytime he got money, he gave it to the band or blew it. He wasn’t starving for success like so many other musicians, didn’t need anyone’s validation beyond them watching him sing onstage until he’d self-cauterized his way into numb and peaceful nonexistence. He mapped a new geography where he could become lost and found, one consisting of music theory and song recipes and the enormous range of equipment and software used to alter sound. He lived in perpetual surprise that he was alive. The band’s gritty black-and-white promo posters showed him grinning among bandmates who glared youthful defiance at the camera. A dark grin that made you wonder. People like David might see him as a Peter Pan, a nearly thirty-year-old boy who never grew up, but that wasn’t true. Deacon’s childhood had died screaming when he was fourteen. His music and performances were all about expressing its loss.

He wasn’t going anywhere, but he’d achieved something like happiness amid the constant melancholy. He’d become a cat.

Honey rolled up to the band’s rehearsal space for the night, storage unit 27, and Deacon smiled at the angry faces of his bandmates reflecting the glare of his headlights.

He cut the engine as Laurie walked over, tall and skinny and dressed in her rocker uniform of black choker collar, tight tank top that showed off her boobs, and ripped sweatpants. Her long, frizzy blond hair was tied up in pigtails, her doll face shadowed with black eyeliner and lipstick. The Joker’s Harley Quinn without the color. She was the lead guitarist and the band’s sound witch, a real savant with the effects pedals, an artist by choice but an engineer and nerd by birth.

Laurie was your gal if you wanted a specific juxtaposition of frequencies across the ears that biohacked the listener’s head by synchronizing their brain waves to three to eight hertz, the operating frequency of dreams and meditation. Or if you needed reverberation to express a binaural beat entraining gamma waves to inspire insight and expand consciousness, which was always part of their opening and closing numbers.

Stain the brain was Deacon’s motto. Laurie’s was to train it with music mainlined like a drug. She wanted to re-create the Mozart effect—an escalation in spatial-temporal reasoning among some people after listening to the great composer’s music—as the Sad Cat effect with her own secret recipes. She was a disciple of My Bloody Valentine and studied everything from chakras to Tibetan chants to the punk band Vision Quest. She played with pedals, whammy bars, didgeridoos, and singing bowls, always searching for the perfect mind-altering frequencies.

“Christ,” she said as he rolled the window down. “You smell like Auschw

itz.”

“Nice,” sighed Deacon. This was how Laurie talked. He was used to it.

“We’re pissed off.”

He held up his songbook. “And I wrote a concept album about a cult.”

“What?” She reached for it. “Let me see—”

“With your eyes, not your hands, lady. It’s raw.” He opened the door and got out to arch his back in a dramatic stretch. He was bone tired.

“Then how are we going to work together?”

“I have to do this one alone,” he said.

“You’re writing an album about a cult without me?” Laurie looked like a kid uninvited to a birthday party.

“The music is all yours. But the words are mine.”

She scrutinized him with her Kewpie-doll face. “This one is personal for you, isn’t it? That funeral you went to up in Bakersfield. You’re holding out on me.”

He smiled. “Good things come to those who wait.”

She sighed. “All right. Now face the music, or they’ll pout all night.”

“Sorry, guys!” he called out. “Foreal!”

“Fuck you, Deacon,” the keyboardist shouted while the drummer raised his sculpted, tattooed arms to give him the double finger.

“Real nice,” he said. “Hey, Laurie. Quick one for you. Joy’s Yamaha can do organ sounds, but how close is a keyboard to the real thing?”

“You mean like a Hammond B3 with a rotary speaker cabinet?”

“I’m thinking more like a pipe organ.” The B3 used tone wheels instead of air moving through pipes to produce sounds.

“I don’t know. Tone wheel, though, yeah, you can get real close. You could play around with the Yamaha Reface. You could also check out Hammond’s XK-3c, which is pretty good at imitating a tone wheel. There are some others.”

Deacon thought about it. “So with the right gear it’s possible to at least approximate the same ambiance.”

“Unless you want to buck up and buy a real pipe organ and then lug it to gigs, yeah. Why are you so interested in organs now?”

“Because the album tells the story of a doomsday cult. The type that makes the apocalypse a self-fulfilling prophecy. I’m thinking we might need a church vibe for some of the songs. The kind of sound that fills a room.”

“What’s the message here, with this album? What are you trying to say?”

Deacon considered how to put it. Like his friends, he didn’t regard the Family of the Living Spirit as a cult, not before it moved to Red Peak, anyway. The contradiction had always fascinated him, leading him to believe maybe there wasn’t a contradiction at all.

He said, “A Christian group becoming a death cult has a terrible beauty to it. A certain logic, if you take it all seriously.”

Laurie’s face lit up at the idea. She put a high value on anything that stuck society in the eye and made people uncomfortable about their treasured myths. She especially enjoyed anything creepy and dark, and doomsday cults neared the top of the list.

Deacon didn’t care about that. He wasn’t even sure he believed the contradiction anyway. What he really wanted to do was capture the essence of an even deeper, far more terrible contradiction, one that had possibly nudged a childhood friend inch by inch into a spiral of suicidal depression. A question he wanted to ask every single person who would one day listen to his new album.

If God appeared in front of you and told you to sacrifice your own child with a knife, the way he told Abraham to kill Isaac, would you do it?

5

PRAY

2002

Deacon squirmed with excitement as he finished his breakfast. Today was going to be the best day ever. A new family was coming to the farm, which included two kids about his age. More kids multiplied the drama, the complexity of alliances, the range of games one could play after finishing the day’s chores.

Mom fluttered around him, tidying up for the Reverend’s visit. Physically, mother and son made an odd pair. Deacon was lanky and tall for almost twelve, Mom short and round. The main thing they shared was a love of music. Deacon sang and was already a fair hand at the guitar. While his talent was budding, Mom’s had fully grown. When she played the organ in the Temple during worship, people felt the Holy Spirit. As for the Spirit, she could make it dance.

Mom eyed the remains of his breakfast. “Finish up so you can get to your chores.”

“Almost done.” Deacon raised his glass, which was still half full of milk.

She pursed her lips, as she was onto him stalling on the days Jeremiah Peale visited, and returned to making everything perfect. While her back was turned, he set his glass back down. She started to sing, delicate and clear as crystal, though hearing her required some intimacy, as she had a quiet voice.

The cabin’s front door sounded with a polite rap. Mom again pursed her lips at Deacon, who raised his glass and made a show of slurping. Taking a moment to fuss over her appearance, she answered the door.

“Good morning, Reverend. Come in. We’re just finishing breakfast.”

Jeremiah Peale stomped into the house. “Am I too early?”

“Not at all. Would you like some tea?”

“Thank you, no.”

Deacon stared at the Reverend. The man was physically big, with a barrel chest and large hands calloused by farming. His presence was even bigger, filling whatever room he was in, whether it was a cabin or the Temple.

He’d combed his hair in a neat side part that was already threatening to break loose over his forehead as the day’s heat rose. On his wide face, he wore a Cheshire cat smile, half choir boy and half rascal.

He beamed that smile on Deacon. “How goes it, boy?”

“I’m well, thank you, sir.”

“Not to mention taller. Every time I turn around, you young ones get bigger.”

The Reverend founded the Family after the 9/11 attacks, which he’d interpreted as a sign. History was coming to an end, and Jesus was on his way back after being gone two thousand years. He didn’t know the exact time and date of Christ’s return, only that he was certain it would happen. After all, Jesus had promised he’d come back, it said so right in the Bible, and the Bible never lied.

Here in this lush valley in the Tehachapi Mountains, the border of the San Joaquin Valley and the Mojave Desert, this man had built a community that would serve as a fortress and model of joyful Christian living in a dying and sinful world. If nothing else, he always said, that was something worth doing.

“Finish your milk, Deacon,” Mom said, her eyes on Jeremiah, “and then you can go outside and get to your chores.”

Deacon picked up his glass again. “Okay, Mom.”

The grown-ups went into the adjacent living room. The Reverend settled into the easy chair while Mom perched prim and proper on the edge of the couch, pen poised over her notebook. They talked about the hymns he wanted in this week’s services. As the Temple organist, she needed to know what he planned for music.

Whenever she looked up at the Reverend, she blushed all the way to her roots and glowed. Deacon liked how happy he made her. After a texting teenager ran a red light and smashed into Dad’s car when Deacon was little, Mom had been sad until she and the Family found each other. The group had given her faith that Dad’s death had purpose and meaning and mystery, and belief he was still alive.

The Reverend smiled at him again. Busted. He gulped the last of his milk.

“Something on your mind, boy?”

He froze like the proverbial deer in the light. He’d been thinking that if Mom ever married the Reverend, he’d be just fine with it.

“When I grow up, I want to be a preacher too,” he blurted.

“It’s a noble calling. The hardest job you’ll ever love.”

“Maybe I could help the new family feel at home. Is there anything special I could do?” He could write a song for them, play it on his guitar.

“You have a fine heart. You care about people, like your mama. So just be yourself, boy.” The Reverend winked

.

“Run along now, Deacon,” Mom said. “The day’s waiting for you.”

“Okay!” He ran to the door to slip into his runners, and bolted.

When the new family arrived, the mom had received a warm welcome, while the kids got drama. David, the new boy, ran off and hid until Emily found him in a supply closet. She’d gone inside and closed the door, and they’d talked so long that Deacon grew bored and went home for supper.

Over breakfast the next morning, he had a brainstorm and gained permission from his mom to act on it. He’d give the new kids the welcome they should have received. After clearing his plate, he went to his room to put on the suit jacket he wore to church.

In the bathroom, he admired himself in front of the mirror. “I just wanted to see how you were all doing,” he told his reflection. “So, how are you settling in?” He cleared his throat. “Oh, hey, how are you? How’s everything going so far?”

He reached to comb his shaggy mop into a side part with his fingers, but stopped himself. No need to overdo it. The Reverend had told him to be himself.

Another great day waited, the best yet.

Outside on the grassy commons, he greeted the sunrise with a grin. Few people wandered about, as most had started work for the day. He had about an hour before he had to start his chores.

“Good morning, Freddie,” he called out sunnily.

Freddie Shaw was seventeen and therefore didn’t have to be called mister. The kid was a mechanical genius and kept the farm’s machinery working. From each according to his ability, to each according to his need was a Family motto.

Freddie looked up from the engine of the truck he’d been servicing, and chuckled as he wiped his forehead with a grimy rag. “Morning, Reverend.”

Deacon faltered but kept walking. Maybe he didn’t look as cool as he thought. He’d wanted to impress upon the new kids that he was an aspiring spiritual leader, but now he wondered if he looked silly. Maybe he should go back to put on his normal duds, but then Freddie would see him and know why he’d changed.

Our War

Our War The Children of Red Peak

The Children of Red Peak Hara-Kiri_a novel of the Pacific War

Hara-Kiri_a novel of the Pacific War The Killing Floor

The Killing Floor The Infection

The Infection The Infection ti-1

The Infection ti-1 Silent Running: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 2)

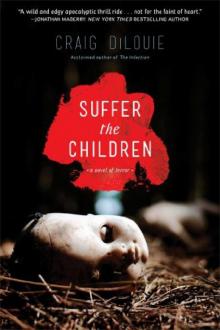

Silent Running: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 2) Suffer the Children

Suffer the Children Crash Dive: a novel of the Pacific War

Crash Dive: a novel of the Pacific War Pandemic r-1

Pandemic r-1 Over the Hill: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 6)

Over the Hill: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 6) Battle Stations: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 3)

Battle Stations: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 3) This Is the End: The Post-Apocalyptic Box Set (7 Book Collection)

This Is the End: The Post-Apocalyptic Box Set (7 Book Collection) Hara-Kiri

Hara-Kiri Hara-Kiri: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 5)

Hara-Kiri: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 5) Contact!: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 4)

Contact!: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 4) Tooth And Nail

Tooth And Nail One of Us

One of Us