- Home

- Craig DiLouie

The Infection Page 3

The Infection Read online

Page 3

“Is killing them murder, Reverend?”

“No,” Paul says.

♦

Ethan takes out his dead cell phone and stares at it intently, wishing it would ring, before returning it to his pocket. He thinks of Philip, sweaty and grimy, sitting in the back of the Bradley with his tie neatly knotted at his throat and his briefcase open on his lap. As the disaster unfolded, the businessman tried for days to call his broker to buy stock in home security and healthcare companies. He drooled over the killing he would make shorting the airlines. He saw home-based power generation as the next big thing. He speculated about pharmaceuticals and trucking and water and agribusiness. The other survivors listened politely, blinking.

Philip’s broker in New York would not answer the phone, making him steadily more anxious. Philip said economics was simply the study of who got the pie. Infection, like the Screaming, was just another economic shock creating new winners and losers, and those who could shift their investments from the losers to the winners quickly would earn the biggest return. But that required a broker who would answer his goddamn phone. It seemed particularly important to him that he convince Anne of his theories, but Anne would listen wearing the expression one usually brings out when rubbernecking a crash, and say nothing.

Philip started shouting into the dial tone, demanding share prices in Remington and Glock and Brinks. Then the grid failed and he lost his signal. He was cut off now and became quiet and morose. In Wilkinsburg, while picking through the ruins of a convenience store, he saw a copy of The Wall Street Journal with the wrong date, sat in the ashes, and let the Infected take him.

♦

They found the dead man in a dark corner, his feet sticking out from under a tarp, which they now pull back to reveal a desiccated corpse sitting with its legs spread and the top half of its head exploded up the walls behind it. The corpse wears a brown uniform. This man was an employee of the Allegheny County sheriff’s office. His gun is missing. Somebody has taken his shoes.

Killed, or killed himself.

Wendy kneels next to the corpse and unpins the man’s star-shaped badge.

“What are you doing?” Sarge asks.

“Collecting dog tags,” she says tersely.

The soldier nods.

Anne approaches, her rifle slung over her shoulder, and tells them dinner will be ready in a few minutes.

“Does this place remind you of anywhere in particular?” Sarge says, watching her closely.

Anne looks around at the garage as if seeing it for the first time.

“I think I was born in a place like this,” she says.

Sarge nods.

She adds, “We need to talk about that tank.”

“We should have followed it,” Wendy says.

“The tank was going to the Children’s Hospital,” Sarge tells them. “Just like us.”

“An isolated unit, then,” Anne says, nodding. “Just trying to stay alive.”

“That tank was the first evidence of a functioning government we’ve seen in days,” Wendy cut in. “It was a patrol. We could try to find the base where it came from.”

“No,” Sarge says. “The tank has no base. It is going to the hospital to shell it. That tank is going to rain fire on it with every bomb and bullet it’s got.”

“That can’t be true.” Anne is at a loss for words, it’s so absurd. “Why?”

“Containment. They were ordered to do it. You have to admire the dedication even while you laugh at the stupidity. The hospital was overrun nine days ago and Infection has already spread far and wide. But just a few days ago the military shifted from containment using non-lethals to use of deadly force, so they ordered the hospitals, the source of Infection, to be attacked. The tank commander is only carrying out his orders, even if they came a week too late. Its infantry escort is gone now, its base has probably moved and every resentful shit-bird in the city is apparently trying to kill it, but that tank is going to complete its mission.”

“How sure are you about this?” asks Anne.

Sarge shrugs. “I know how the military has been responding. It fits.”

“So what do we do?” Wendy says.

“We find another hospital. Preferably one that isn’t being bombed.”

“There’s Holy Cross, across the river,” Anne offers.

“Which river?”

“The Monongahela. In the south.”

They have already previously decided that a hospital is the ideal place to settle for several reasons. First, few people would even think to enter one. They are taboo places. Charnel houses. Unclean. After the Screaming, the Infected were picked up from the ground one by one and brought to hospitals, but there was not enough room, so the government requisitioned schools, hotel ballrooms, indoor arenas and similar spaces to accommodate the millions who had fallen down. The hospitals were filled to overflowing. The screamers were stacked like cordwood in the corridors. So many people required care that medical students were handed licenses and retired healthcare workers were drafted. When the Infected woke up three days later, they slaughtered and infected these people, making the hospitals epicenters for death and disease.

The hospitals are rich in resources, however, and they are defendable. Specifically, they have medical supplies, food and water, lots of space and emergency power. And most of the Infected are long gone, compelled to search for fresh hosts for their virus.

Anne adds, “It’s worth the risk.”

The three nod. The group’s next move has been decided.

♦

Wendy touches Anne’s elbow and motions her aside. The two women walk through the service garage, seeing everywhere the evidence of work abandoned suddenly by the mechanics.

“What branch did you serve in?” Wendy says.

Anne shakes her head almost imperceptibly.

“I appreciate your service,” Wendy continues. “But I am the highest civil authority here. It would help if you acknowledged me as such in front of the others.”

Anne regards the cop in the gloomy half-light from the camp’s LED lanterns.

Wendy clears her throat and adds, “We have to function as a team.”

“You know, I didn’t believe in evolution before,” Anne interrupts, inspecting a car muffler lying on the floor like the bone of a giant animal. “But now I do. We are natural selection in action. So many other people died because they wanted to die. They fought tooth and nail to survive but they didn’t want to live while everybody they knew and loved died or became Infected.”

“You’re talking about survivor’s guilt,” Wendy says, nodding.

“Yes. We all have it. The question is whether you’re going to let it kill you.”

Ethan calls out to them, telling them supper is ready.

Anne turns to go back, pausing to add, “You go on taking crazy risks like you have to prove your leadership, and you will let it kill you.”

Wendy stares at the woman for a moment, unable to speak.

“I’m just doing my job,” she says finally. “I’m responsible for these people.”

“That’s fine with me. I don’t care who’s in charge. I’m just trying to find refuge and help the group find it, too.”

“So you will acknowledge me then,” the cop presses.

“No,” says Anne.

♦

Before the world ended, the cop woke up alone at five each morning in her small apartment in Penn Hills. She showered, ironed her uniform and wolfed down an energy bar. She put on her crisp short-sleeve black shirt over a clean white T-shirt, then stepped into her black pants. She attached her badge and pins before pulling on her bullet-proof vest and Batman belt.

She reported to work at six in the morning carrying a tall cup of coffee. After roll call, she started up her patrol car, told the dispatcher she was in service, and drove to her patrol territory. Most of the time, the dispatcher called her about dogs barking, suspicious characters walking through backyards or hanging around play

grounds, loud music and domestic violence. She pulled over speeders and drunks, wrote up accidents and graffiti, gave people lifts to the nearest service station when their cars broke down. She isolated crime scenes and canvassed homes for witnesses to murders. Every so often she did a “park and walk,” where she left her squad car and patrolled on foot for ninety minutes. Some days, she was so bored she could barely stay awake. Other days, so busy she ate nothing but donuts and Slim Jims. She watched other cops act aggressively to control every encounter, and tried to imitate that impersonal, in-your-face attitude. After several months on the job, she began to view most people as idiots who needed to be saved from themselves. She wrote tickets, threatened wife beaters, ate dinner in her car, waited for the next call on her radio. After a twelve-hour shift, if she did not have to work late, she went home.

Even though a large part of her job involved either cleaning up or eating other people’s shit, she was proud of being a police officer and loved her job. Then the world ended and she never felt so important or needed. A part of her rejoices in being a cop in a lawless world. In the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is king.

♦

The survivors share corned beef cooked on the Coleman stove with stewed tomatoes and served on paper plates on a hot bed of cooked brown rice, with canned pears for dessert. As much as they are sick of food out of cans and crave fresh fruit and vegetables, they wolf down their meal. The Kid feels a sudden piercing stab of regret as he realizes he will probably never eat Buffalo wings again. It is odd to focus on such a trivial thing when faced with so much loss but he realizes that he is going to have to mourn the lost world one little bit at a time.

After dinner, Paul lights a cigarette and smokes in silence while the others take turns having sponge baths behind a nearby car. Wendy, breathing angrily through her nose and holding back tears, gets the solar/crank radio working.

“—not a test,” a soothing, monotone, mildly British-sounding voice says. “This is the emergency broadcast network. This is not a test. Today’s Homeland Security threat level is red for severe risk. Remain indoors. Obey local authorities. Avoid individuals displaying suspicious or aggressive behavior.”

One by one, the survivors chime in with the announcer, almost chanting, “When encountering military units or law enforcement officials, place your hands on your head and approach them slowly and calmly. Do not take the law into your own hands. Respect life and private property—”

Sarge turns off the radio. “I think we can all agree that today was as bad as yesterday.”

They nod glumly.

“On the other hand, Sergeant,” Paul says, “I think we can also safely say that we’re all still here. I would consider that one for the win column.”

“Amen, Rev,” the Kid says.

Anne returns from her sponge bath and nudges the Kid’s shoulder.

“Here’s that new toothbrush.”

♦

Outside, they hear the howl of the Infected and the tramp of hundreds of feet. Distant gunshots and screams. Then it is so quiet they can hear the blood rushing through their veins. In the dim light of a lantern, Ethan accepts a sleeping pill from Wendy and dry swallows it. He lies on his bedroll in a T-shirt and shorts and relives his last conversation with his wife and child, and then becomes groggy. His last coherent thought before falling into a deep sleep is a vague recollection of a Greek myth in which sleep and death are brothers.

His nightmares are exhausting trials of lurid colors and feelings, extremes of good and evil, and symbols of guilt. He finally dreams of a warm evening at home, his wife pink and happy in a cherry bathrobe, holding their daughter on her lap in a rocking chair next to the toddler bed. The familiar ritual of getting ready for sleep. But the walls turn dark and sooty with ash and cluttered with graffiti tags and photos of missing children. A bullet hole appears in the window behind his wife’s head. She is still smiling as she smells her daughter’s hair, but her face has turned gray, her mouth and chin stained black. His little girl is not moving. He does not know if she is breathing.

His wife licks the back of her head, as if grooming her. As if tasting her.

FLASHBACK: ETHAN BELL

Nine days ago, Ethan woke up in an empty bed with his heart pounding against his ribs. He found his wife in the bathroom, putting on mascara in front of the mirror with her mouth open, while Mary sat on the floor imitating her. Ever since the Screaming three days earlier, he found himself panicking when he did not know where his family was. He suffered nightmares in which they fell down screaming. He tried not to think of his students who actually did.

“I need coffee,” he said. “Where are you going, hon?” He added a quick wave and grin at his daughter. “Hi, Mary!”

“Work,” said Carol. “I have to work today.”

“Hi Daddy,” said Mary.

“But you weren’t going to go to work until Thursday.”

“Uh, today is Thursday, Ethan.”

“No,” he said, then smiled broadly for Mary, who was suddenly staring at him acutely, worried that he was upset. “You should stay home again today. A lot of people are doing that.”

“Ethan, we talked about this,” his wife said, her own smile genuine. “We’re all still freaked out but the country has to get moving again. Too many things are up in the air. And we need money coming in. We have to eat.”

Mary said, “No talking.”

“The schools are still closed,” he pointed out.

“They need room for the screamers.”

“Don’t call them that.”

Carol snorted. “You actually want me to call them SEELS?”

“We should show a little respect, that’s all,” he grumbled.

Sudden Encephalitic Epileptic Lethargica Syndrome, or SEELS, was the more formal, if overly broad, term popularly used by scientists to describe the mystery disease. Other than naming it, scientists knew very little about it. Some said it reminded them of Minor’s Disease, with its sudden onset of pain and paralysis caused by bleeding into the spinal cord. Some wanted to explore exploding head syndrome, others frontal lobe epilepsy, others maladies related to the functioning of the inner ear. A group of scientists wrote a letter to the President demanding widespread sampling of air, soil, water and people for novel nanotechnology agents, warning that the worst may be yet to come.

Equally puzzling was the ongoing exotic symptoms exhibited by some of the victims of the new disease. Echolalia, for example, the automatic repetition of somebody else’s sounds. Echopraxia, the repetition of other people’s movements. And, in some cases, “waxy flexibility,” the victim’s limbs staying in whatever position they were last left, as if made of wax. Nobody could explain why some people had these symptoms and others did not, just as they could not explain how the disease chose its victims, nor how it spread so quickly around the globe in a single day. There were very few real facts, only hundreds of theories that tried to force these facts to make sense.

“Look, Ethan. They’ll reopen the schools soon. In the meantime, why not go to the school and see if you can volunteer at the clinic? A lot of people need care around the clock.”

“Maybe,” he said.

“It might do you some good,” she said tartly, cutting him down with a single a glance at his tangled, curly red hair and stubble. “Get out in the sunshine a bit. It’s time, Ethan.”

“All right, I probably will,” he lied. He had no intention of leaving the house. “Leave Mary here, then. Last night, when I was up watching some TV, there was some kind of rioting going on all over the west coast. I’d like to keep her close to home.”

“We live in Pennsylvania. And Mary misses her friends at daycare. They’re holding a special candlelight vigil today for the SEELS.”

“No talking!” said Mary, upset that her parents were talking to each other and not to her. “My talking!”

Carol got down on one knee to talk things out with their two-year-old, asserting their adult right to have a conver

sation, but the fact was the conversation was over.

Ethan made a cup of coffee, kissed them goodbye, and went back to bed.

He woke up, feeling uneasy, to the sound of sirens in the distance. Sitting up, he yawned and pulled on a T-shirt and a pair of sweatpants. Sunlight shined into the second floor bedroom picture window, which offered a spectacular view of downtown that had cost them an extra twenty thousand dollars on the house list price. Ethan and Carol moved to the city from Philadelphia during the previous summer, and she insisted on having a view. It was early afternoon. He needed another cup of coffee. Then he glanced out the window and saw plumes of smoke rising up from downtown, over which helicopters swarmed. There were a lot of sirens.

“Goddammit, I knew something bad was happening,” he said, searching frantically for the TV remote before finally finding it under the bed. He clicked the television on and pulled on his glasses, blinking.

Riots spreading throughout the country, across the world in fact, focused on the hospitals and the clinics, following the same path as the screamer virus. Panicked mobs firebombing the clinics. Families of victims arming themselves and taking up positions outside the clinics. And the screamers, who had lain in a catatonic state for three days, were waking up and apparently committing acts of violence.

“Holy crap,” Ethan said, his heart racing.

He dialed his wife, but all circuits were busy. Should he drive to the daycare and get Mary? Then drive to the bank and get Carol? What if she were already driving here? What if she were trying to call him right now? He hung up the phone and paced, racked by indecision.

Our War

Our War The Children of Red Peak

The Children of Red Peak Hara-Kiri_a novel of the Pacific War

Hara-Kiri_a novel of the Pacific War The Killing Floor

The Killing Floor The Infection

The Infection The Infection ti-1

The Infection ti-1 Silent Running: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 2)

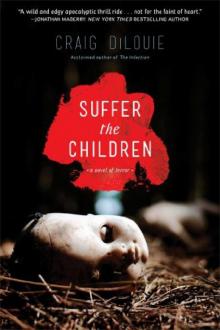

Silent Running: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 2) Suffer the Children

Suffer the Children Crash Dive: a novel of the Pacific War

Crash Dive: a novel of the Pacific War Pandemic r-1

Pandemic r-1 Over the Hill: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 6)

Over the Hill: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 6) Battle Stations: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 3)

Battle Stations: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 3) This Is the End: The Post-Apocalyptic Box Set (7 Book Collection)

This Is the End: The Post-Apocalyptic Box Set (7 Book Collection) Hara-Kiri

Hara-Kiri Hara-Kiri: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 5)

Hara-Kiri: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 5) Contact!: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 4)

Contact!: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 4) Tooth And Nail

Tooth And Nail One of Us

One of Us