- Home

- Craig DiLouie

Our War Page 25

Our War Read online

Page 25

“Are you her boyfriend?” Jack said.

The kid wore a dreamy smile. “I’m Jacob. We have rules.”

“We just wanted to say hi,” Alex said.

Jacob set his laser eyes on him. “You don’t belong here.”

The girls moved on to the next house. The blonde glanced over her shoulder to give Alex a parting smile, which he returned. “We didn’t mean any harm.”

“You aren’t one of us. You don’t believe.”

Alex barked a laugh. The boy’s words unsettled him. He wanted to punch that dreamy, smug smile. “Whatever you say, dude.”

Gunfire erupted in the distance. Alex tightened his grip on his AR-15, but there was nothing to shoot at.

“Who’s shooting?” Jack said. “What is that?”

The firing was happening down the street, behind the front line.

Jacob only smiled and said nothing.

“Come on. Let’s get out of here.” Alex turned and started walking.

His friend caught up, his face turning pale. “That shooting is happening at the clinic. Should we tell the sergeant?”

“Look at his face. Mitch already knows.” Just thinking about it made Alex sick. “These people are maniacs.”

“Who would do something like that?”

He turned for one last look at the pretty blonde. To his surprise, she was looking at him. She glanced side to side before giving him a little wave.

Alex didn’t wave back.

FORTY-EIGHT

In Terry’s room, Aubrey worked on his laptop while he sprawled on the bed reviewing his interview notes. Rafael inspected his photos on his digital camera.

The keyboard buzzed as her fingers raced like hummingbirds across the keys. A world of information was at her fingertips again. With the electricity shortages and almost nonexistent Wi-Fi, she’d learned to live without the Internet, but it was good to be back.

Google was still working. The network backbone was still operational, though many websites it once connected had gone dark or were no longer being updated. The major media was online, a comforting sight, and she caught up on the top headlines. The Mexican Army blew up part of the Texas border wall. California pacified Bakersfield. A bombing in Times Square killed eight people. President Marsh said he might return to the Ottawa peace talks.

Aubrey glanced through it all and then conducted a search for any mention of child soldiers being used in the American war.

“Nothing in the mainstream media,” Aubrey announced. “A few bloggers are talking about it.” She rattled off a list of states.

Terry peered at her over the rims of his reading glasses. “Now we need to confirm it.”

“Confirm?”

“You know the industry proverb. If your own mum tells you she loves you, check it out.”

“I already confirmed that child soldiers have been reported in these states.”

“Call Gabrielle and see what she’s got.”

She sighed. “Can I use your phone?”

The reporter handed it over. “Mind my minutes.”

“Okay, Dad.” Aubrey thumbed Gabrielle’s number.

The UN worker answered. “I’m in the hotel. I’ll be right down.”

“She’s on her way,” Aubrey said after the call disconnected. “I bookmarked the blogs in case you want to make contact with them.”

While she waited, she opened Facebook and entered another search. A few people were talking about child soldiers. She followed various social networks, absorbing opinions. The majority of pages she found stopped within a few months of the outbreak of war.

In those that were still active, the civil war was being fought here too, with words, just as it had long before the cultural cold war turned hot. Social media had promised to bring people together but only helped polarize them along new tribes isolated in separate echo chambers.

Aubrey’s next search found Gabrielle Justine’s page, which was filled with people wishing her well and asking if she was okay. Her albums showed photos of her with university friends skiing at Mont-Tremblant and kayaking in Saguenay. She always stood at the center of the group, fresh-faced, no makeup, smiling shyly at the camera. She had plenty of friends, some of them male, all of them protectors. They were in love with her, Aubrey guessed; Gabrielle was like some rare and beautiful bird that had a broken wing.

Every day, she marked herself as safe in Indianapolis.

The page gave Aubrey an idea. She did another search and swiveled the laptop so Terry could get a better view of the screen. “Check this out.”

He leaned for a closer look. “What did you find?”

“Hannah Miller.”

Hannah had told them her mother’s name and hometown. While Miller was a common surname, there was only one Linda Miller in Sterling.

Terry eyed the images as she scrolled through them. Linda seemed a vibrant woman and caring working mother. She’d posted about the trivialities of life and a few major passions, such as baking. While she was sparing in posting photos of her children, they appeared in a few vacation and holiday series along with her husband, Harry.

He said, “I can’t believe it’s the same girl.”

Aubrey pointed at the screen. “That’s her brother, Alex. I met him. He’s fighting for the other side on the same stretch of front.”

In the most recent shots, Hannah hammed it up while Alex scowled, aching to be somewhere else but without any idea where he wanted to be.

“Brilliant. Perhaps—”

“Don’t even think it. They’ll shoot me this time.”

“Would they shoot me?”

“Right now, I’m pretty sure they would.”

“All right, sod it then. Bookmark that page for me, would you? I’m having a brainstorm. What if we print out a few of these photos for Hannah, and tell her about her brother being on the other side?”

Rafael looked up from his camera. It was great journalism.

“No,” Aubrey said.

“I let you drive, but don’t forget who’s running this story.”

“Just no. Okay? She’s been through enough. I’ll let her know once the fighting dies down, but it’ll be off the record.”

Terry looked to Rafael for support. The Frenchman shrugged.

“All right. We’ll do it your way, but only because we’re against the clock.”

A knock at the door. Aubrey went over and let Gabrielle into the room. The UNICEF worker launched into a hug.

Aubrey stiffened in alarm at the sudden contact. Then she returned it with a smile. “How are you?”

Gabrielle handed her a sheet of paper. “Some numbers for you.”

Aubrey scanned the list of Indy militias. The figures with asterisks were considered reliable. The rest were pure estimates, either because the militia wouldn’t talk or because they might be hiding something. Plenty of question marks, unknowns.

She handed the sheet to Terry, who scrutinized it.

“Right now, we’re estimating about twelve hundred children are serving in militias just on this side,” Gabrielle said. “There are many unknowns—”

Terry held up his hand. “UNICEF is estimating twelve hundred child soldiers in Indianapolis, just on the Congressional side. Am I correct?”

“Yes.”

“That’s all I need.”

“We caught wind it’s happening in other states,” Aubrey said.

Gabrielle blew out a sigh. “This next part will probably get me fired.”

Before Aubrey could offer some options, the UNICEF worker handed her another sheet of paper showing a list of American states.

Next to thirty-one of them, a checkmark.

“Jesus.” She passed the sheet to Terry, who grinned.

“Jackpot,” he said.

“This is based on UNICEF humanitarian assessments submitted in forty-four of the fifty states,” Gabrielle explained. “So. Is this enough?”

“This is plenty,” Aubrey told her.

“My peop

le are working on more media appearances. I’ll do what I can at my end. I only hope it all comes to something.”

She left out the sentence hanging in the air, I hope it’s all worth it. Gabrielle was risking her job. Aubrey her liberty, possibly her life.

Aubrey swiveled Terry’s laptop. “A reminder why we’re doing this.”

The UNICEF worker crouched to study a photo of Hannah and Alex at the Indiana Dunes State Park. They stood on a beach in their swimsuits, Lake Michigan a rich blue behind them. Photographs from another time and place, another world.

A single tear coursed down her cheek.

Rafael’s camera clicked. Aubrey threw him a sharp look.

“Sorry.” Gabrielle wiped her eyes. “I’m a little emotional right now. I’m moving out of the hotel tomorrow.”

“Where are you going?”

“The Peace Office found me an apartment to rent. The CERF budget is limited, and, well…”

“What?”

Gabrielle glanced at Terry. “I didn’t want to feel like a tourist anymore.”

The journalist didn’t deliver the cutting remark Aubrey expected. Instead, he smiled. “You’ve come a long way in a short time, UN.”

Aubrey smiled too. They all had. Her and Terry’s words, Rafael’s images. They had everything they needed now. It was going to be one hell of a story.

A story that might change everything.

Gabrielle stood to go. “Thank you. For everything.” Again, that gratitude that came from deep in the heart.

This time, Aubrey accepted it.

FORTY-NINE

In the record store where he’d set the platoon HQ, Mitch propped his leg on a crate. He wasn’t getting any younger, and his body took longer to bounce back from punishment. Nearly a week after the offensive, his ankle and back were still killing him.

Bud, the platoon radio/telephone operator, or RTO, sat on a lawn chair facing a rickety card table, relaying orders to the far-flung units in the bulge. Next to his station, a strategic map hung on the wall with duct tape.

The story it told was promising. Second Platoon didn’t end up crossing the river, but Mitch knew ops rarely worked out as planned. You shot for the stars and grabbed the moon. This was how wars were won, moving the ball a few yards at a time.

I should be satisfied, he thought.

The radio operator said, “You mind if I light up, Sergeant?”

“It’s a free country, Bud.”

“It’s slow going out there. At this rate, it’ll be tomorrow by the time the Angels deploy and our guys take up their new positions.”

“If that’s what it takes,” he growled, “then that’s what it takes.”

Bud took the hint and smoked his cigarette in silence.

Mitch wasn’t satisfied at all.

Every minute of delay allowed the libs to reinforce and entrench, but that wasn’t what bothered him.

The Angels had dragged the libs’ wounded out of the clinic and shot them like dogs. It disgusted and enraged him enough he’d made a point of staying clear of them out of fear he’d switch sides and start another war.

Later, he worried maybe they were onto something.

Shock and awe. Maybe the only way to win the war was to inflict a Biblical level of destruction on the enemy. Strike them with sheer terror. Total war. The stakes were high enough to justify almost anything.

Still, even after a year of fighting, the libs never felt quite like the enemy. Even now, he had a hard time hating them. He saw them more as spoiled, ungrateful children than an evil needing to be destroyed.

Mitch stood with a grunt and limped over to inspect the map. Drawn in different-colored grease pencils, squares marked the patriot and lib positions. Red for Liberty Tree, blue for the Free Women, and black for the First Angels. In two days, the Angels would attack and find out if God really was on their side.

The door opened to admit a blast of light and cold. Alex and Jack walked into the store and froze at the sight of their sergeant.

“Sorry,” Alex said. “We didn’t know this was HQ.”

Mitch pinned them with his stink-eye. “What are you boys up to now?” Looking for another secret place to smoke their cigarettes, probably.

“Just exploring.”

Aside from Bud, the HQ staff was off getting their supper. He saw no harm in them looking around. “You like records?”

The floor was covered in vinyl. The sleeves had all been salvaged for kindling.

The kids glanced at each other and knelt to inspect the mess.

“I don’t know any of these bands,” Alex said.

“What’s the one you got in your hand?” Mitch asked him.

The kid read the label. “A Lot About Livin’. And a Little ’bout Love.”

“Alan Jackson. That one takes me back. ‘Chattahoochee’ is a great song.”

“What kind of music is it?”

“Country, son. God’s own music.”

“Yeah.” The kid put the record back on the floor. “No.”

Mitch snorted. “You kids don’t know what’s good. Rap ain’t even music.”

“How old were you when this came out?”

“Hell, I was about your age. The summer that year, my dad drove me and my brothers into the woods with a truck full of tools. We built our own log cabin.”

A simpler time. Together, they’d cleared the land and marked the footprint, then poured out the concrete and set the piers. Every day over that long, hot summer they worked, laying joists and flooring, joining logs, framing the roof. That was how Dad did things, with his own hands and know-how, and screw the permits and codes.

“Wow,” Alex said. “You’re lucky. I never did anything like that.”

“My brothers didn’t feel so lucky. After a while they complained they were giving up their entire summer. Dad caught wind of it and disciplined all of us.”

“Even you?”

“Yup. Even me.”

“But that’s not fair,” Alex said. “You weren’t the one complaining.”

“And I didn’t complain about getting punished either. Dad was teaching me that life ain’t fair. It don’t owe me a thing. And something else. If you want something, you work for it. You pull yourself up by your bootstraps. And if you agree to do something, you do it, no excuses. A man is defined by his word.”

Years later, Mitch joined the Army to serve his country while his brothers moved away to its far corners, as if trying to put as much distance as possible between themselves and the old man. They didn’t even come back for Dad’s funeral.

Mitch hadn’t hated his father. He’d respected him. He wanted the man to be proud of him. And Dad was. Though he didn’t show it, Mitch knew. His father had taught him life was hard, and if you wanted to be a man, you had to be hard too. Mitch had always accepted this severe teaching as a form of love.

He was glad Dad died before America became a place where you weren’t even allowed to say, “Merry Christmas.”

“My dad isn’t as tough as you,” Alex said.

“That’s the America we live in.”

“He’s strong, just in a different way. I didn’t see that until a little while ago.”

It was good to see the kid respect his old man. For Mitch, it was what the war was all about. Respect for the old ways. Self-respect.

The door creaked open. Donnie tramped in looking glum, followed by Tom.

“What now?” Mitch said.

“The cathouse closed down,” Donnie complained.

“Which one?”

The soldier lay on the floor and glared at the ceiling. “All of them.”

Tom leaned against the wall. “The guys told me the Bible thumpers rousted the girls. They’re gone.”

“The Angels? How do you know it was them?”

“Who else would paint crosses and WHORE all over the walls?”

Mitch didn’t visit the cathouses himself, but he allowed it. He knew how important it was to morale. Men loved to fi

ght, and after they fought, they wanted to fuck. The patriots were a volunteer army and needed to blow off steam.

The First Angels had only just arrived. Already, they’d pissed off his entire platoon and impaired their combat effectiveness. Half the neighborhood was covered in crosses.

“Plenty of female flesh just ahead of us,” Bud said at the radio. “I’ve been picking up their chatter.”

“That does it, Sarge,” Donnie said. “I’m switching sides.”

Mitch frowned. During the battle, the Free Women had used kids as runners for communication. If they were using shortwave radios, the police were supplying them. He wondered what else the IMPD was sending over.

“Can I listen in?” Jack said. “Just let me hear them talk.”

Bud glanced at Mitch, who nodded. He adjusted the radio until he found the Free Women’s frequency on the police band.

A woman’s voice: “—runners will be swinging by with food and ammo.”

The RTO grinned. “Most of the time, they don’t even use a code.”

“Or they want us to think they don’t,” Mitch said. “Either way, we should put a man on listening in on their communications.”

Another voice: “I hope they hurry. This war diet is bad enough as it is.”

Laughter on the radio.

Jack smiled. “Can we say hello, Sergeant?”

Tom snorted. “Didn’t you hear what he said? If we break silence, we’ll let them know we’re listening in.”

“It’s all right,” Mitch said. “Who wants to go first?”

Donnie scrambled off the floor and snatched the radio from Bud’s hand. “Hey, baby, what are you doing tonight? Over.”

The radio went quiet. The men laughed. Mitch smiled. If they couldn’t get their nut, they could have a little fun. It was worth tipping off the Free Women their communications were being monitored. They weren’t going to learn much anyway. Meanwhile, the squad had fought hard. The boys had earned a boost.

A female voice said, “Putting a bullet in your fascist ass. Over.”

The men laughed again.

“I do like ’em feisty,” Tom said.

“Come on,” Donnie said. “Isn’t your type supposed to make love not war?”

“You’re right about that, lover boy,” the woman’s voice purred. “Why don’t you come on over here? There’s a lot of women dying to meet you.”

Our War

Our War The Children of Red Peak

The Children of Red Peak Hara-Kiri_a novel of the Pacific War

Hara-Kiri_a novel of the Pacific War The Killing Floor

The Killing Floor The Infection

The Infection The Infection ti-1

The Infection ti-1 Silent Running: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 2)

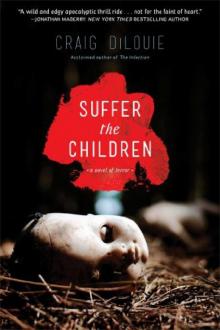

Silent Running: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 2) Suffer the Children

Suffer the Children Crash Dive: a novel of the Pacific War

Crash Dive: a novel of the Pacific War Pandemic r-1

Pandemic r-1 Over the Hill: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 6)

Over the Hill: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 6) Battle Stations: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 3)

Battle Stations: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 3) This Is the End: The Post-Apocalyptic Box Set (7 Book Collection)

This Is the End: The Post-Apocalyptic Box Set (7 Book Collection) Hara-Kiri

Hara-Kiri Hara-Kiri: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 5)

Hara-Kiri: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 5) Contact!: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 4)

Contact!: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 4) Tooth And Nail

Tooth And Nail One of Us

One of Us