- Home

- Craig DiLouie

The Infection ti-1 Page 22

The Infection ti-1 Read online

Page 22

To the survivors, the camp represents the Time Before. If they drive into that place, they will rejoin the human race. They will be like astronauts returning home after years in space. But the world will not be the same. The Time Before is gone and anything resembling it is a mirage and possibly a trick. The truth is if they go down into the camp, they will surrender their liberty in return for protection, and they are worried about the cost. Right now they are being chased hard by the devil, but it is the devil they know.

Sarge sighs. “It’s a chance. Anybody got any better ideas where to go?”

Nobody does.

“Anne would know what to do,” Todd says.

“Anne ditched us, Kid,” Sarge says bitterly. “We waited around for two days and she didn’t come back. We barely made it out of there alive. She’s either dead or on the road. Either way, she already made her decision and has no say in ours.”

“Okay,” Todd says.

“So that’s it, then,” Paul says, nodding. “We’re going in.”

Wendy snorts. “We have no choice.”

♦

The Bradley cruises down the road past fields filled with the stumps of cut trees and burning piles of cleared brush. Scores of pale department store mannequins wearing designer fashions strike surreal poses across the smoky wasteland, their torsos tied to stakes and old street signs planted at regular intervals, some lying in the dirt among rags and scattered plastic limbs. A hundred yards from the road, several figures in bright yellow hazmat suits load bodies into the back of a municipal garbage truck, pausing in their work to stare at the armored fighting vehicle as it zooms past.

The camp looms close now, piled across the horizon and emitting waves of white noise and sewage smells and wood smoke. The vehicle roars past a concrete pillbox from which the barrel of a heavy machine gun protrudes, swiveling slowly to follow its progress. A man wearing a T-shirt and camouflage pants steps into the road and waves at them, motioning them to stop, but the rig keeps rolling, sending him sprawling into the ditch. Near the gates, more in hazmat suits are tossing body bags from the back of an olive green flatbed truck into a deep, smoking pit. They pause in their work, staring, as the Bradley comes to a halt in a cloud of dust and sits idling in the sun.

The man in the camo pants jogs up panting for air. He slaps his hand against the Bradley’s armor.

“Open up in there, goddammit,” he shouts.

After several moments, he adds, “If you think we’re going to let you into the camp without you telling us who you are, you’re crazy. So what’s it going to be?”

The single-piece hatch over the driver’s seat flips open and the gunner pops his head up, grinning. Moments later, the hatch on the turret opens and Sarge emerges wearing a scowl.

“We’re looking for Camp Defiance,” he says.

The man laughs. “You came to the right place. And you would be?”

“Sergeant Toby Wilson, Eighth Infantry. I’ve got one crew and four civilians inside. We were told it was safe here.”

“We’re still here, ain’t we?” The man turns his head and roars, “Open the gates! Got a military vehicle coming in!” He winks. “Welcome to FEMAville, Toby.”

The gates slowly grind open, pulled by soldiers with rifles slung over their shoulders, and the Bradley lurches forward in low gear, following a uniformed woman directing them where to park using hand signals. The area smells like diesel fuel and decaying garbage. Other soldiers press in, gawking at the vehicle and its cannon.

Sarge blinks, startled, as they burst into cheers at this symbol of American might.

They are still clapping as the survivors emerge blinking into the sunlight, wide-eyed and smiling awkwardly.

The area appears to be some type of checkpoint and distribution area bustling with activity. The Bradley sits parked between a beat-up yellow school bus and a Brinks armored car. A massive pile of bulging plastic garbage bags awaits disposal next to several rows of body bags. A large truck stacked with cut logs sits next to a cluster of large yellow water tanks, one of which is being coupled to a pickup truck. Men in overalls are unloading salvage from the back of a battered truck covered with a patchwork of tiny scratches made by fingernails and jewelry. Light bulbs hang from wires strung between wooden poles. The Stars and Stripes sways from one of these wires like drying laundry, big and bold, making Sarge suddenly aware of a lump in his throat.

He looks down at the cheering, hopeful boys and wonders if this might be home.

A man pushes his way through the throng, extends his hand and helps Sarge down from the rig. He is a large man with a square build and salt and pepper hair and silver Captain’s bars.

“Welcome to Defiance, Sergeant,” the man says. “I’m Captain Mattis.”

“Sergeant Tobias Wilson, Eighth Infantry Division, Mechanized, Fifth Brigade—the Iron Horse, sir,” Sarge answers, saluting.

The Captain grunts. “You’re the first I’ve seen from that unit.”

“I’m afraid I’ve lost them, sir.”

“And your squad?”

“KIA over a week ago, sir. Pulling security for a non-lethal weapons test.”

“Non-lethals,” Mattis says sourly. “I almost forgot we even tried it. Seems like a year ago. You’ve been on the road with these civilians since then?”

“Pretty much. I trained them, and they did most of the fighting.”

“I’ll be damned,” Mattis says, sizing up the others. “Were you all in Pittsburgh?”

“We got out just ahead of it.”

“A horrible thing. I stayed overnight there once, you know, years ago. Loved the rivers and all the bridges. The old neighborhoods. Beautiful city.”

“Yes, sir, it was. So what is the situation here?”

Mattis smiles. “You rest up. I’ll bring you up to speed after your orientation, Sergeant.”

Sarge notices that the grinning soldiers are collecting weapons from the other survivors.

The Captain adds, “Now please surrender your sidearm.”

♦

Wendy climbs onto the school bus and collapses into one of the seats, fighting the urge to curl up into a ball. For the last two weeks, she has lived with her Glock always locked, loaded and within easy reach on her hip. She now feels its loss as if it were an amputated limb.

Sarge sits next to her, his hands fidgeting.

“Are we under arrest or something?” she whispers to him.

“I don’t know,” he says. “They said we have to go through some sort of orientation.”

She chews her lip, wondering. Orientation could mean just that—the people who run the camp want to tell them about who runs it, what the rules are, how to collect rations—or it could be a euphemism for something else, perhaps something sinister. Sarge looks worried, not a good sign. The windows have been painted black and covered in layers of chicken wire, making the interior as dark and claustrophobic as the Bradley. And without the protective weight of her gun at her side, she is ready to assume the worst.

The school bus roars to life and begins rolling forward, trembling violently as it passes over a series of deep potholes.

Wendy reaches for Sarge’s large hand and clasps it in hers.

“Did the soldiers tell you anything?” she asks him.

Sarge shakes his head. “I don’t know who’s in charge.”

“What do you mean?”

“I mean I literally don’t know who’s in charge here—FEMA, the Army, some other branch of the government. Those guys you saw at the gate weren’t from a single unit. I recognized patches from at least six different outfits. Some Army, some National Guard. The highest-ranking officer on the scene—that captain I was talking to—was a logistics officer in an ordnance company. The only real clue I saw was the flag when we came in. It was a U.S. flag.”

“All right,” she says. “But if they’re Army and you’re Army, why’d they take your gun?”

“I don’t know, Wendy.”

“I don’t

like this. Not knowing.”

He squeezes her hand and says, “I don’t like it either.”

“At least we’re all still together.”

Wendy flinches at a loud thud, followed by another. Somebody is throwing something heavy at the bus. It reminds her of the monster bashing their vehicle as they struggled to flee the Pittsburgh fire. She gasps and digs her nails into Sarge’s hand, which he accepts without protest. The soldiers at the front stand up, glaring, fingering their rifles. The window across the aisle explodes and angry shouting and dusty sunlight penetrates the bus. Wendy half stands in her seat and catches a glimpse of camping tents and people through the jagged hole.

“Take your seat, Ma’am,” one of the soldiers says, a clean-shaven kid with large ears protruding from under his cap. “Please, it’s for your safety.”

Wendy sits, shaking her head in wonder.

“Volleyball,” she says, feeling almost giddy with relief. “I saw some teenagers playing volleyball outside.”

“That wasn’t a ball that hit us,” Sarge says. “Somebody was throwing bricks or rocks at us. Something is wrong here.”

“It can’t be all wrong if kids are playing volleyball,” she says.

“People play volleyball in prison,” Sarge tells her.

The bus stops and the driver kills the engine. They sit quietly for several minutes, waiting for something to happen. The heat is oppressive. The smell of diesel exhaust slowly dissipates, replaced by conflicting odors of cooking and open sewage. They hear a mother shouting at her child to be careful. Somebody is playing a guitar.

The door opens and a woman enters the bus carrying a clipboard, her face partially obscured by a green bandana. Her blue eyes glitter against her sunburned forehead. She pulls the bandana down, revealing a young, pretty face set in a bright smile.

Wendy grunts with surprise. The camp appears to be run by teenagers.

“I’m Kayley,” the girl says. “I will be your orientation instructor.”

♦

The survivors are led into a classroom inside a brick school building. Kayley stands at the front of the room, by the chalkboard, while they take their seats. The window blinds are open, allowing sunlight to fill the space and providing an outside view of several women taking a smoke break while another inventories a pile of boxes.

Ethan pauses at the teacher’s desk before finding a seat. His classroom had been like this one, clean and neat but low on budget and behind the times in terms of technology. The main teaching method was lecture using a green chalkboard, erasers and lots of chalk. For a little excitement, maybe an overhead projector with transparencies. He remembers how much he loved the squeaky sound a stick of chalk made on the board as he wrote equations for his students. He loved everything about the job, in fact. That, and his relationships with his family, had defined him.

How quickly things change, he thinks.

How would you solve for x?

Answer: You try to kill it.

His finger throbs with pain. He pops another painkiller.

A part of him realizes that he could start over here. The camp appears to offer a second chance. If they provide schooling to kids, maybe he could even become a teacher again. Putting his skills to work here is a duty as real as Wendy’s wish that she were still a cop. One might think teaching kids math during the apocalypse would be a waste of time, but the opposite is true. Kids should continue learning, preparing for the future. Otherwise, there is no future and the war against Infection is already lost. The other way lies barbarism.

He will never teach again, however. He knows this. Even if the plague and the fratricides were to end tomorrow, he still cannot imagine it. That part of him is as broken as the world.

The truth is the only reason he is here is because of the slim chance he might find his family among the camp’s residents. This hope, as thin as it is, has become his strongest reality. Everything else is illusion. He will keep searching until he finds them. He will search forever. That is what he does now. That is who he is.

Todd flops into the desk next to him and slouches, scowling. “I just can’t get away, I guess,” he mutters.

“Ready for some algebra?” Ethan says with a wink, hoping to rib him.

“I liked algebra,” Todd tells him. “It’s school I hated.”

A man walks into the room, talks quietly with Kayley for a few moments, and then leaves. Immediately, a group of people enter in a cautious daze.

“You are all survivors of Pittsburgh,” she tells them. “You are not different from each other. You are all the same. At one time, you were neighbors. Welcome each other.”

The survivors pause, sizing each other up, and nod before taking their seats. The newcomers are filthy and exhausted. One of them sobs quietly as she hugs a sleeping toddler against her chest. Another puts his head down onto his desk and immediately falls into a fitful sleep. Dust floats in the sunlight around them. They smell like ashes.

“Welcome,” Kayley says. “Welcome to Camp Defiance. You are safe here, in this room. This is a safe place and you’re okay.”

The survivors quiet down and look at her hungrily.

She says: “After the Screaming, the Federal Emergency Management Agency established a series of forward operations posts across the country to coordinate Federal support of local authorities. Camp Defiance was one of them, although back then it was simply called FEMA 41.”

After the Screaming turned into Infection, she explains, the camp was almost overrun, but word had gotten around about its existence, and people poured in from all over southern Ohio. The refugees helped keep the camp going and now it is run by a mixture of Federal, state and local government people and protected by a mixed bag of military units.

“Today, the camp has a population of more than one hundred and thirty thousand people, and is constantly growing,” she tells them, pausing to let that sink in. “I worked in a refugee camp for the Peace Corps for two years overseas. The ideal size for a camp like this is twenty thousand. It’s nothing short of a miracle this place is functioning as well as it is.”

Ethan suppresses the urge to whistle. A hundred and thirty thousand people is a tiny fraction of the population in this region before Infection, but it represents a chance. Somewhere, in this teeming horde, his wife and baby girl might be living, safe and sound.

Kayley spends the next fifteen minutes describing how they will be processed. Newcomers to the camp must go through a brief medical exam and register, she tells them, to receive resident cards. Food and water may be collected at food and water distribution centers. Skilled workers may be offered jobs by the government paid in gold, and receive priority access to housing and bonus allotments of food and water. The camp also has a health center and scattered health posts, pest houses, cholera camp, schools, markets and cremation pits for disposal of the dead.

“Does anybody have any questions so far?”

“I do,” Ethan says. “What kind of records do you keep? I’ve got family missing.”

Kayley nods. “Locating lost loved ones is a big priority for us. Tell the people at registration while you’re being processed, and they’ll help you out. We keep a record of every person who has ever entered this camp. They also have contacts with other camps in Carollton, Dover, Harrisburg and other places.”

Ethan leans back in his chair, satisfied.

“I’ve got a question,” Sarge says loudly, standing. “What are you hiding here?”

Kayley smiles at him. Her face shows no signs of surprise.

♦

The survivors bristle at Sarge’s tone. A moment ago, they were disoriented, listening to Kayley in a lethargic daze, struggling to absorb everything she was telling them. Now they are alert and taut as deer that smell a predator in a sudden shift of wind. They watch Sarge and Kayley closely, their hearts racing and their breath shallow as they once again, automatically, tread the tightrope between fight and flight.

After several moments, Kayley says

, “Can you be more specific?”

Sarge blinks. “Well, for one, why did you take our guns?”

Wendy glares at Kayley, wondering the same thing and wishing she felt the reassuring weight of the Glock in her hand right now. She feels electrified by urgency and confusion. She has complete faith in Sarge’s instincts but he sprang this confrontation without telling her; she has no idea how to back him up.

“Sergeant Wilson, almost everybody in this camp is armed,” Kayley is saying. “We all know that Infection spreads like wildfire. If one person got the bug, it might bring the entire camp down. We are on the constant lookout for Infection and must be ready to act quickly if we see it.”

Sarge crosses his arms. “I’ll ask again, then: Why did you take ours?”

“Your weapons were taken for the time being because, quite often, certain newcomers do not take to orientation. We do not have the means to enable new residents to slowly transition from the dangerous world outside to the relatively safe oasis that we have created here. Some people cannot accept the sudden change and become upset and irrational.”

“I can see why,” Sarge says. “It’s like a police state around here.”

“Yes and no. We are actually rather thin on policing. Surely you don’t really think this camp could function without the consent of its residents. But it is true that we are a society that is under siege. It is different being here than out there on the road.”

“If we are not prisoners, you would let us leave if that’s what we wanted.”

“You are not prisoners, but neither can you simply come and go from the camp as you please, for obvious reasons. Every time somebody enters the camp, there is the possibility of Infection or some other disease being imported. We cannot allow that.”

“You’re not answering my question,” he says.

“The simple answer is you can leave any time you like. But if you do, you cannot come back. Is that a satisfactory answer?”

“We can leave with all our gear?”

“If a resident decides to leave, they can go with either what equipment and supplies they brought or its equivalent value, which is the law.”

Our War

Our War The Children of Red Peak

The Children of Red Peak Hara-Kiri_a novel of the Pacific War

Hara-Kiri_a novel of the Pacific War The Killing Floor

The Killing Floor The Infection

The Infection The Infection ti-1

The Infection ti-1 Silent Running: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 2)

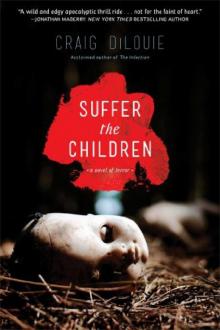

Silent Running: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 2) Suffer the Children

Suffer the Children Crash Dive: a novel of the Pacific War

Crash Dive: a novel of the Pacific War Pandemic r-1

Pandemic r-1 Over the Hill: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 6)

Over the Hill: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 6) Battle Stations: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 3)

Battle Stations: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 3) This Is the End: The Post-Apocalyptic Box Set (7 Book Collection)

This Is the End: The Post-Apocalyptic Box Set (7 Book Collection) Hara-Kiri

Hara-Kiri Hara-Kiri: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 5)

Hara-Kiri: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 5) Contact!: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 4)

Contact!: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 4) Tooth And Nail

Tooth And Nail One of Us

One of Us