- Home

- Craig DiLouie

One of Us Page 2

One of Us Read online

Page 2

“I’m just curious about them,” Jake said. “More curious than scared. It’s like you said, Mr. Benson. However they look, they’re still our brothers. I wouldn’t refuse help to a blind man, I guess I wouldn’t to a plague kid neither.”

The teacher nodded. “Okay. Good. That’s enough discussion for today. We’re getting somewhere, don’t you think? Again, my goal for you kids this year is two things. One is to get used to the plague children. Distinguishing between a book and its cover. The other is to learn how to avoid making more of them.”

Jake turned to Amy and winked. Her cheeks burned, all her annoyance with him forgotten.

She hoped there was a lot more sex ed and a lot less monster talk in her future. While Mr. Benson droned on, she glanced through the first few pages of her book. A chapter headline caught her eye: KISSING.

She already knew the law regarding sex. Germ or no germ, the legal age of consent was still fourteen in the State of Georgia. But another law said if you wanted to have sex, you had to get tested for the germ first. If you were under eighteen, your parents had to give written consent for the testing.

Kissing, though, that you could do without any fuss. It said so right here in black and white. You could do it all you wanted. Her scalp tingled at the thought. She tugged at her hair and savored the stabbing needles.

She risked a hungering glance at Jake’s handsome profile. Though she hoped one day to go further than that, she could never do more than kissing. She could never know what it’d be like to scratch the real itch.

Nobody but her mama knew Amy was a plague child.

Three

Goof saw comedy in everything. He liked to look on the sunny side. He enjoyed seeing the world differently than other people, which wasn’t hard considering his face was upside-down. When he smiled, people asked him what was wrong. When he was sad, they thought he was laughing at them.

He raised his toothbrush in front of the bunkhouse mirrors. The gesture looked like a salute. “Ready to brush, sir.”

He commenced brushing.

“Hurry up,” the other kids growled, waiting their turn.

Goof clenched his teeth and brushed faster but for twice as long. “’ook at me, I am b’ushing my ’eet’ ’eal ’ast.”

His antics had earned him his nickname and gained him some status in a community sorely lacking in entertainment. He liked to make the kids laugh. When that failed, annoying them to make himself laugh.

Then Tiny, the biggest kid at the Home, stomped into the bathroom. He elbowed one of the smaller kids aside and took his place at the mirrors.

Goof shut up and tilted his head to gargle and spit. He could only annoy so far, particularly around kids like Tiny. The Home forbade violence, but the teachers looked the other way as long as nobody disrupted its workings. If you went to a teacher to complain about a kid punching you, you were liable to get a smack and be told it was part of your education.

No matter. He’d done enough for one day. Today had been fun. The Bureau had sent out an agent for the annual interviews. Goof had tried a self-deprecating creeper joke that fell on deaf ears, the agent being the earnest type. Having failed to make him laugh, Goof decided to be annoying the best way he knew how.

“I’m Agent Shackleton,” the government man had said while lighting a cigarette. “Bureau of Teratological Affairs. You—”

“Know the drill, don’t you by now,” Goof finished. “I sure do, sir.”

The man scowled. “All right, that’s good. This year’s different, Jeff. I’m here to find out—”

“If you’re special,” Goof said. “No, I ain’t, I’m sorry to say.”

The man’s frown deepened. “How do you keep—”

“Doing that? I don’t know what you mean.”

“You keep—”

“Finishing my sentences.”

“Are you aware—”

“You keep doing that? Doing what, sir?”

Then he’d howled with laughter, a grating sound the teachers once told him sounded like a mule getting screwed where the sun don’t shine.

Agent Shackleton had smiled like he was in on the joke. “Thank you, Jeff. We’re done here.”

Goof had discovered his gift about six months ago. He’d finished Ms. Oliver’s sentences all through history class. Her jaw practically hit the floor. Everybody was cracking up. They couldn’t believe it.

Just wait until they all heard he’d stuck it to a Bureau man. He was about to become a hero of legend around here.

He undressed and climbed into his bunk with a satisfied sigh. Around him, the kids chattered as they got ready for bed. The old frame creaked as he settled on the grimy mattress. The lights clicked off minutes later.

Hero of legend, he thought as he drifted into sleep.

A hand shook him awake. “Rise and shine.”

The room was dark. It was still night.

“What’s that? What’s going on?”

He recognized Mr. Gaines standing at one side of bed, Mr. Bowie on the other. Teachers from the Home school.

“Get your duds on,” Mr. Gaines told him. “We’re taking a walk.”

Goof hopped down and pulled a T-shirt and overalls onto his skinny frame. He laced up his weathered boots. “If this is about the whatever, I’m sorry.”

The men didn’t laugh. There was nothing funny about this. When teachers woke you up at night, you were headed to Discipline. The other kids either kept snoring or lay rigid in their bunks, pretending to be asleep.

“Let’s go,” Mr. Gaines said.

“I didn’t do anything, honest.”

“That’s what they all say.”

The problem kids went to Discipline. The wild ones who broke the rules. No windows. A single chair bolted to the concrete floor, under a bare light bulb.

“I was just kidding around with the Bureau man,” Goof pleaded. “I didn’t mean nothing by it. Come on, Mr. Gaines. You know I ain’t one of the bad ones.”

Mr. Bowie placed a gentle hand on his shoulder and shoved, knocking him off balance. “Move it, shitbird.”

Goof stumbled outside on trembling legs. He was rarely outside at this hour and couldn’t help looking up. The sky was filled with stars. A great big world out there that didn’t care about his fate.

Lights blazed in the big house. Another world, a world of pain, awaited him. Brain had warned him to keep his special talent to himself. He’d said it would get him into the kind of trouble he couldn’t get out of. Lots of kids had talents now, and it was important to keep them a secret from the normals. Why didn’t he listen?

“Look at him,” Mr. Gaines said. “Shaking like a fifty-cent ladder.”

“He’s sweatin’ like a whore in church,” Mr. Bowie said.

Goof had heard kids in Discipline sat in the chair facing a big ol’ rebel flag. A giant blue X on an angry red field. As if to tell you that you were no longer in the USA but had entered a different country. A secret place with its own rules and customs. A place in history where they could do anything they wanted.

“No,” he begged. “Please don’t take me there.”

“Man up, boy,” Mr. Bowie said and gave him another shove.

A black van stood in the driveway in front of the house. Mr. Gaines walked over to it and opened the back doors.

“Your chariot awaits,” the teacher said.

“Wait,” Goof said. “I ain’t going to Discipline?”

“It’s your lucky day.”

Mr. Gaines waited for him to climb inside and take a seat in the back. Then he reached up and cuffed one of Goof’s hands to a steel bar running along the ceiling. “So long, Jeff. Don’t forget to send us a postcard.”

Mr. Bowie laughed as the doors slammed shut.

A man in gray overalls started the van. The headlights flashed on, illuminating rusted oil drums stacked by the utility shed.

“Hello, Jeff,” said a familiar voice from the passenger seat.

“Mr. Shackleton?”<

br />

“We’re going to take a long drive. You might as well sleep.”

“A drive? Just a drive? Is that true?”

A part of him thought this was all a big joke. The van’s doors would click open again, and Mr. Bowie would yank him out and drag him to the big house.

The van pulled away from the Home and started up the dirt track that led to the county road. Goof took a ragged breath and expelled it as a laugh.

As the Home disappeared in the dark, his relief slid headlong into another kind of panic. The Home wasn’t a nice place, but it was, well, home.

“Where are we going, sir?”

“Someplace nice,” Shackleton said. “You’ll like it.”

The agent leaned his seat back as far as it went and laid a fedora over his face.

Goof had rode in the back of one of the Home’s pickups during farm days, but never inside a van like this. He tried to imagine he was being chauffeured. He was a secret agent on his way to catch a plane to Paris.

The fantasy didn’t last. He was still shaking like that fifty-cent ladder.

“What’s your name?” he asked the driver.

The man didn’t answer. A bug splatted against the windshield.

“Mister, I hope we’re stopping soon. I got to pee already.”

Still no answer.

“Now I can’t quit thinking about it,” Goof said. “I’m gonna pee my pants soon.”

“We’ll stop when we stop,” Shackleton said from under his hat. “Until then, Jeff, shut your trap and try to get some shut-eye.”

Goof fidgeted in his seat. He didn’t know how the agent expected him to sleep after the scare he’d just had. He wondered if he’d ever sleep again.

Then his eyes fixed on the agent’s fedora, and he fell in love. He’d never seen one like it before except in old movies. He wanted one for himself. Goof pictured walking into the mess hall wearing it, the kids all going nuts.

That’s when it hit him.

Goof was on his way to a different world, and he’d probably never again see his friends or home.

Four

Breakfast, the usual slop eaten around wooden tables in the Home’s mess hall. Dog picked at his porridge and waited for his friends to show up. Today, they were learning ag science, which meant a day working out at the farm. His favorite thing about school besides Sundays off to spend with his friends.

He wasn’t happy about it today, though. He wasn’t happy about anything. He hadn’t slept well, his mind wild with disappointing thoughts. Birdsong had woken him up early. A family of thrushes outside the window.

The Bureau man had said he wasn’t special and never would be. Said he lived high on the hog in the Home. Told him to get the hell out of his sight.

None of it was fair in the least.

Dog’s mama had abandoned him when he was just a little baby. Other normals had taken care of him since. Sure, they fed him and kept a roof over his head. But high on the hog it wasn’t. Anybody with eyes could see. The Home was run-down and overcrowded, the beds infested. The roof leaked brown water on the floor.

He never asked for any of it. He was unlucky to be born.

The bench groaned as Brain settled his bulk on it. The teachers said Brain looked like a lion fucked a gorilla. His bestial appearance contrasted with his small, delicate hands and eyes glittering with surprising intelligence.

But not special, it seemed. The government didn’t take Brain, who was the smartest person he knew. Dog could run fast, faster than Brain, maybe faster than anybody alive, but the Bureau set the bar too high for them all.

Wallee and Mary showed up next and took their seats with their breakfast trays. No surprise they were still here. Wallee was a big sac of blubber that could barely talk. Mary, a stunted and homely girl with an imbecilic face. She was the only kid who didn’t have a nickname.

Dog sometimes wondered if she wasn’t a plague kid but instead just plain retarded. Brain said maybe the normals stuck anybody they didn’t want in the Homes. Everybody they rejected ended up here, from the kids to the teachers. Brain and Dog watched out for her and kept her safe.

“You seen Goof this morning?” Dog said.

“They took him last night after lights out,” Brain said.

“Where did they take him?”

“I can’t say, Dog.”

“The Bureau man said something about a special place.”

“I warned him to keep his mouth shut,” Brain said.

“You’re gonna be next,” Dog said, angry that Brain had faked his way out of being taken. “You always talking the way you do. You think you’re so—”

He stopped. He didn’t know why he was attacking Brain. He was just mad. He was afraid the government would take all his friends, and he would be alone. Left behind. Stuck in the Home the rest of his days, the only one who wasn’t special.

Brain’s gentle face hardened with shock and hurt.

“Sorry,” Dog said. “I don’t mean any of that.”

“I’m smart enough to shut up when I have to. Goof wasn’t.”

One of Dog’s earliest memories was Brain quizzing him after the Bureau sent out somebody to question the kids. Tell me what happened, Brain said at four years old. What the man asked, what you answered. It’s important you tell me exactly what you remember. Even back then, Brain talked like an adult. Every year since, the same: Brain wanting to know the questions, how they answered. That way, he could blend right in, and they could never single him out.

Which also wasn’t fair. Brain was special, but he hid it.

“At least he’s going somewhere other than here,” Dog said.

“Careful what you wish for,” Brain said. “For all we know, they kill the special ones. Throw them in a gas chamber. Fear motivates everything they do.”

Dog remembered jumping to his feet after the Bureau man told him to get the hell out of his sight. The man’s rudeness was like a whip cracking. When he’d jumped, Shackleton went stiff in his chair. The man had been afraid of him, if only for a second. Dog could smell it. It got his dander up.

You don’t get to be scared, he’d wanted to shout.

But he’d liked it. Some deep part of him fed on it. He felt strong. A little taste of power for a boy who had none. You want to be afraid of me, sir? Would you think I was special if I showed you some fear?

“I just wish I could get out of here,” Dog said. “Be a grown-up allowed to do what I want. Work for a living. Watch TV at night. Go to bed when I want.”

“What do you want to be when you grow up?” Brain said.

“I’d like to own my own farm like Pa Albod. Grow my own crops. Make an honest living.”

Dog planned to work for Pa Albod long enough to buy a plot and become a sharecropper. Then expand his holdings until he had his own farmstead.

Wallee slurped his food. “Want to be sher-iff.”

Mary said nothing. She stared off into the blank space where her mind lived most of the time.

“What about you, Mary?” Dog said. “What do you want to be, you can do or be anything.”

“Pretty,” she said.

“I’d like to be a doctor,” Brain said. “But that will never happen. Do you know why they teach us agricultural science four days a week? So we can serve the masters as cheap farm labor the rest of our lives. The only future they’ll let us have. Men with no rights, no future. They’ll put us on reservations like they did the Creek Indians who used to live in these parts. It’ll be just like the Home.”

Wallee grimaced. “Not sher-iff?”

“Maybe. Sure, they’ll let us police ourselves. Like at Auschwitz.”

Wallee’s face ballooned into a smug smile. “Sher-iff.”

Dog moved the porridge around his bowl as he considered Brain’s gloomy prophecy. He didn’t want to believe it, though he’d always known it to be true. The only way out was to be special, but he wasn’t special. The government man said he wasn’t and never would be.

Bra

in watched Dog eat and wished his friend could understand. But Brain lived in a lonely world in which nobody truly understood him.

Dog would never see the truth until the system crushed him. Chipped away at his humanity until only a monster was left. A monster with nothing to lose.

As for Brain, he’d understood everything within minutes of his birth.

In photographic detail, he remembered the terror of being born. The first thing he heard was his mother’s screams. The world bursting in lurid dream colors. Confusing, horrible, wonderful.

A man’s blanching face. Wide, watery eyes. The world spun as the doctor presented him to his mother lying in the hospital bed. He stared at her through a blurry squint. She screamed again, saying something he didn’t understand. A bolt of love shot through him. He reached out with his little arms to comfort her.

Then the world spun again, and she disappeared forever.

They took him away and put him in the Home. He’d ached with worry. What had they done to his mama? Was she okay? Why couldn’t he see her? Later on, the teachers taught him language. That was when he learned what she’d been screaming when the doctor held him squirming in his big hands.

Brain got all the education he ever needed during these first moments of his life. He learned what he was, what they were, and that monsters and men were not meant to exist in the same world. If your own mother hates you and drives you away, why should total strangers love you? From the beginning, the masters understood this fundamental truth. They created separate worlds, one for themselves, another for monsters. The system would not end when the mutagenic reached adulthood. The children would grow up to become free folk living in an invisible cage, with no rights or opportunities. Which meant no real freedom at all.

Dog couldn’t understand this now because he thought more with his heart than his mind, and he still had hope. Dog saw the Home as a purgatory to be endured before reaching some promised land. The system would crush that hope out of him. Brain could tell him the truth of their world until he was blue in the face, but some truths people just had to find themselves through experience. And when all Dog’s hope had fled, when it was finally dead and gone, only then would he understand. Only then would he know he had nothing and that having nothing meant you had nothing to lose and everything to fight for. A Spartacus will call to them all, and they will rise up to shatter the walls between the worlds.

Our War

Our War The Children of Red Peak

The Children of Red Peak Hara-Kiri_a novel of the Pacific War

Hara-Kiri_a novel of the Pacific War The Killing Floor

The Killing Floor The Infection

The Infection The Infection ti-1

The Infection ti-1 Silent Running: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 2)

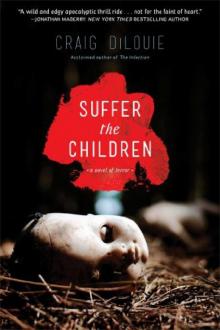

Silent Running: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 2) Suffer the Children

Suffer the Children Crash Dive: a novel of the Pacific War

Crash Dive: a novel of the Pacific War Pandemic r-1

Pandemic r-1 Over the Hill: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 6)

Over the Hill: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 6) Battle Stations: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 3)

Battle Stations: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 3) This Is the End: The Post-Apocalyptic Box Set (7 Book Collection)

This Is the End: The Post-Apocalyptic Box Set (7 Book Collection) Hara-Kiri

Hara-Kiri Hara-Kiri: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 5)

Hara-Kiri: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 5) Contact!: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 4)

Contact!: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 4) Tooth And Nail

Tooth And Nail One of Us

One of Us