- Home

- Craig DiLouie

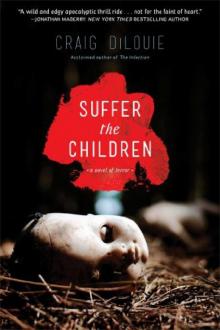

Suffer the Children Page 2

Suffer the Children Read online

Page 2

He said, “Joanie said it was extra safe to play with but we shouldn’t try to eat it because it tasted bad. She was right. It tasted really bad. It was really salty.”

An innocent mistake. Ramona sighed and looked back at the house. The front door with its plastic wreath was closed. The family Christmas tree sparkled in the window. She figured she owed Joan an apology.

Something else to feel guilty about. Add it to the fucking list.

She’d call Joan over the weekend. Maybe call Ross while she was at it. Apologize to everybody for everything. When she had time.

“It’s okay, little man. Don’t cry. Mommy’s not mad. I just hope you learned your lesson.”

“But I want to come back. Don’t be mad at Joanie!”

“I’ll bring you back on Monday. I promise. But first we have to see Santa tomorrow, don’t we?”

Josh perked up a little. “Santa at the mall?”

“That’s right.” She got into the driver’s seat and eyed him in the rearview. “I love you, little man.” She couldn’t hide the exasperation in her voice. “I really do. Are those your new drawings? Can Mommy see them?”

She took the sheets of construction paper and rested them on the wheel. As Josh approached the age of five, his drawings had gone from crude stick figures to highly detailed renderings. He insisted his mother tape every drawing to the refrigerator door and, when that space ran out, the walls of his room. Praising his artwork always cheered him up.

But these new ones were disturbing. She leafed through them quickly with a frown. Black shapes chased fleeing people in every one.

Her son, who normally drew knights and animals, was now drawing monsters.

David

22 hours before Herod Event

David Harris listened to Shannon Donegal’s life story, scribbling notes into her file while ignoring the dull ache in his leg.

She was eighteen, beautiful, and glowing with robust health. In three months, she would bring another life into the world, a baby boy she was calling Liam.

David held a license as a pediatrician, not an obstetrician. He treated children, not pregnant women. When he’d returned to work after the accident, however, he’d started offering free one-hour prenatal consultations to rebuild his patient base.

He considered it an investment. He was beginning to feel hopeful about the future for the first time in a year. Not a lot, but enough to make an extra effort to restore his practice to what it once had been.

Shannon had her own problems, it seemed.

Valedictorian of her class, she’d earned a scholarship to attend George Washington University in the fall, where she would have studied international relations. Instead, at a graduation party, she’d had sex with her boyfriend Phil, who, despite being the football team’s star running back, had no scholarship or real plans. He’d seemed destined to remain stuck here in Lansdowne while Shannon went off to bigger and better things. Two missed menstrual periods later, however, she discovered she was having a baby she wanted but Phil didn’t. Now it was Shannon who seemed destined to remain in Lansdowne, while Phil had left town as fast as his feet could take him.

Little of this story proved relevant in any medical sense, but David listened with polite interest, reminding himself to take his time and make a good impression. He steered the conversation back to her and the baby’s health. Did she smoke? Who was her obstetrician? Were there any health issues she was concerned about?

No health issues, it turned out. Just questions.

“Should I breast-feed or go with formula?”

“I recommend breast-feeding for at least six months. A year is even better. Breast-feeding can prevent allergies and protect the baby from a number of infections and chronic conditions.”

“So Liam and I would pretty much be breast-feeding all day and night, right? What’s the term? ‘Glued at the boob’? I mean, isn’t that the trade-off?”

“To an extent, but not all the time. My wife used a breast pump to store milk, which I fed to our boy in a bottle once per night. That gave her some uninterrupted sleep.”

I’d hug little Paul as he cried against my chest in the boy’s warm, dark room, swaying side to side on my feet and shushing him to get him to return to sleep.

A file drawer slammed shut in the reception area outside his office. Nadine, going about her work and likely eavesdropping. He cleared his throat, forgetting where he was for a moment.

“Oh yeah, I will definitely be exploring that,” Shannon said. “Phil’s gone, but I will have help.” She wrote it down in her notebook. “What about circumcision?”

“There are health arguments on both sides of that question, although the percentages are low for any risks. It’s really a personal decision.”

Shannon winced. “Doesn’t it hurt?”

“A topical cream or some other anesthetic is used.”

“What did you and your wife do?”

David suppressed a frown. He didn’t like to talk about his personal life with his patients, although he’d brought it up. “I’m circumcised, and I wanted Paul to look like me. When I realized that was the only reason we were going to do it, we decided against it.”

“What about shots?” Shannon said. “Did you immunize him?”

“Of course we did.”

“Some people say it can cause autism.”

“Studies have found no link. As a doctor, I rely on empirical evidence. What I can say is if your child is not immunized, he risks contracting a deadly disease.”

“What about the disease itself? You can get measles from the vaccine, right?”

“Not really. The odds of something like that happening are very small. Your baby would already have to have a severely compromised immune system for such a thing to be likely. Again, such a thing is very rare.”

Shannon sighed. “Okay.”

“I like your questions. You came well prepared.”

“I am really, really scared.”

He smiled. She was utterly adorable and far too innocent. “You should be. It’s a very serious thing to bring a life into the world.”

“Then please give me some advice as a father, not as a doctor. What’s the most important thing you’ve learned?”

“You don’t need personal advice from me. Did you have any other medical questions?”

“Come on, doctor. Please? Just one thing. Consider it a question of supreme importance to my mental health.” She held up her notebook and showed him a page filled with her neat handwriting. “Look, I’m keeping a diary of good advice from everybody I know.”

“All right. Well, not to be flippant about it, but my advice is to be careful about soliciting too much advice. No matter how much advice you get about things like keeping your child happy, no one will know your child better than you will. Trust yourself.”

“Wow, I like that,” she said. She wrote it down in her notebook. “Thanks, doctor. There are just so many things to deal with.”

He remembered holding Paul and thinking, Don’t grow up, baby boy. Stay just like this forever. “Millions of women have done it before you—most of them under very primitive conditions. Take it one day at a time, and you’ll be fine.”

“One day at a time, huh?” She smiled. “That’s going to be my mantra every time I think about all those diapers I’m going to have to change.”

“When it’s your child, you don’t care about those things. The fluids, smells, crying at all hours of the night.” His eyes stung, and he turned to stare out the window. Snow fluttered onto the parking lot. “None of it matters because you love this tiny thing with every atom in your body. The biggest problem every parent has is it goes by too fast. Cherish every minute you have with your child.”

Shannon’s eyes welled up with tears. “Oh my God.”

He tried to smile. “Sorry about that.”

“No, it’s really beautiful.” She sniffed and fanned herself with her hand. “Do you have a photo of Paul?”

David

picked up a framed picture of his son from his desk and handed it to her. In it, Paul grinned and held a Tonka truck over his head like a trophy.

“What a cutie. What do you do for day care? Does your wife stay home? If you don’t mind me asking.”

“I, uh . . . Paul passed away, Shannon.”

The girl slapped her hand over her mouth. “Oh. My. God.”

“Almost a year ago. There was an accident.”

She stared at the photo. Tears welled in her eyes. “I am so sorry.”

“No, I’m the one who should apologize. You came here for medical advice, not to become upset.” He cursed his stupidity. The idea of death was infectious; it wouldn’t take long for Shannon, her body raging with hormones, to imagine her own child dying. After taking the photo back, he picked up the phone, punched Nadine’s extension, and asked her to bring a package of public health literature. “I’ll get you some brochures to take home.”

“I was judging you in my head, wondering why you don’t smile,” she said. “You looked so grim. I had no idea this happened. I am such an idiot.”

“Not at all.” He opened a drawer and produced a box of tissues.

“Can I ask what happened?”

Blinding light filled the car and winked into dark just before the BOOM.

“It was . . .”

The world spun and glass shards splashed up the windshield.

“Dr. Harris,” a familiar voice said.

He woke to a hissing sound, his wife still holding the wheel, looking dazed, his leg pierced by a barbed tongue of metal.

“Paul?”

He tried to twist in his seat to look behind him, but his leg exploded in agony.

He gritted his teeth and tried again—

“Paul!”

“David.”

He looked up in surprise. Nadine stood in the doorway of his office. She entered and slapped a handful of brochures onto the desk, glaring at him before turning to Shannon.

“What happened to the doctor is none of your concern,” Nadine said. “It’s a private matter.”

She turned on her heel and stormed out of the office.

“I’m really sorry,” David said, reddening. “She shouldn’t have said that to you.”

“What did I do?” Shannon wondered. “What was that all about?”

“That,” David answered, “is Nadine Harris.”

“Harris? You mean she’s—”

“My wife. Paul’s mother.”

Might as well put it all on the table at this point, he thought.

He doubted, after this visit, that Shannon Donegal’s son was going to become a patient of the grim Dr. David Harris.

Doug

20 hours before Herod Event

Doug Cooper liked that it wasn’t as cold as yesterday. He liked that the trash he picked up today didn’t contain any broken glass or disposable needles. He liked that the bags didn’t rip open and spill rotten meat, asbestos, or shit-filled diapers all over his boots. He liked that no homeowners yelled at him, no cars came close to hitting him, no dogs tried to bite him.

And still it was a shit day, just like all the rest.

When Otis called him into his office after he’d changed out of his work clothes at the end of his ten-hour shift, Doug had a feeling it was about to get a whole lot worse.

He scowled under the grimy brim of his red LOVIN’ LANSDOWNE baseball cap, which the Plymouth County Department of Solid Waste Management handed out last year to all its employees who worked in the city. Broad-shouldered, standing at an imposing six feet two inches, he towered over his supervisor. His stubbled jaw and handlebar mustache made him look comical when he laughed and meaner than a dog when he got angry. Right now, he wore his mean face.

“Grab a seat,” Otis told him, and took a seat himself, leaning back in the creaking chair with his hands folded on his massive belly.

Doug sat and dipped his head to light a Winston. They weren’t supposed to smoke in here but did so anyway when the long, hard day was done. The old office smelled like an ashtray. Doug recognized stacks of yellowing paper on Otis’s desk he’d seen months ago. Nothing ever changed in here except the months and years on the calendar hanging on the wall.

Whatever was on the man’s mind, Doug hoped the conversation would be quick. He had no time for small talk or pictures of Otis’s grandchildren. Joan was putting supper on, and he wanted to get home and see his kids.

“So how are you, Doug?”

“Peachy,” Doug answered.

“Good to hear. I got some news from the County. Some pretty major news, actually.”

“Oh boy, here it comes.”

“Why do you always think the worst? I’m trying to tell you they approved the contract for the Whitley rigs.”

Doug felt a surge of heat in his chest, like heartburn. “I thought that was dead.”

Otis lit his own cigarette and waved the match. “It’s alive, and it’s here.” His face turned an alarming shade of red as he coughed long and hard into his fist. “Better get used to it, Doug. They’ll be delivered in the early part of the year. We should be seeing the first vehicles on the road by springtime.”

Every day, Doug worked his ass off as part of a two-man sanitation crew—one man driving the truck, the other dumping trash into the rear of the rig, where it was compacted. The new Whitley trucks that the County wanted side-loaded waste using automatic lifts. The rig had a mechanical claw that grabbed the garbage can and dumped its contents right into the hopper.

It sounded great—unless you were a sanitation worker hoping to keep your job during a time of shrinking budgets. The automatic rigs needed only one man to operate them.

When Joan had gotten pregnant with Nate, Doug had sworn he’d do anything to provide for his family. He became a waste collector. At the time, he’d thought it was one of the safest professions on the planet. Sure, it was a tough and dirty job, but everybody needed it done, a good union protected it, and it couldn’t be offshored.

He’d never anticipated that a new type of garbage truck might make him obsolete.

Spring was only four months away.

He stood, suddenly filled with nervous energy that he didn’t know what to do with. “Shit, Otis. What about my job?”

“Sit down, Doug. Nobody’s going to lose his job. The County will reduce head count through normal attrition. Guys move, others retire, and they won’t be replaced. That’s it.”

Doug expressed his skepticism for that news with a snort. Whatever the politicians had told his boss, when it came to budget cuts, they had a way of changing their minds once they smelled blood.

Otis planted his elbows on his desk. “Look, that’s what they’re saying, okay? Don’t go telling people otherwise, Doug. I don’t need a goddamn panic.”

“I don’t gossip like some schoolgirl, Otis. But I will be checking with the union to see what kind of guarantees the County is offering in writing. I got mouths to feed at home.”

“You’re not seeing the big picture here. Why is there always a conspiracy theory with you? You got to look on the bright side.”

“Yeah?” Doug asked, mean face in full effect. “And what’s that?”

“Sanitation is being revolutionized,” said Otis, as if it were a fast-moving, glamorous field. “Faster, cheaper, better. Trash pickup at a thousand homes a day, and the driver never leaves the cab. If the garbage isn’t in the bin, it stays where it is. No rain, no rats, no stink.”

Otis looked almost wistful about it. Doug guessed the man wished he had these rigs during the thirty-five years he’d spent hauling garbage in the rain and snow.

It was sad to witness. Otis had been a hairy son of a bitch back in the day, a hard drinker and a bar fighter, but now he just looked worn out, ready to retire himself. Doug always thought he’d end up just like him, marking time on a calendar in some crappy office and managing the next generation of hairy SOBs. He wondered now if he’d even get that privilege, thanks to the Whitley truc

ks.

What was he going to do if he lost his job? How would he face Joan and the kids, who depended on him? The very thought made him grind his teeth. What good was a man who couldn’t provide for his own?

Doug had grown up in hard times. He’d known hunger as a child—not the I-wish-I-had-more-treats bullshit but real, gut-gnawing hunger. His biggest wish was to give Nate and Megan the childhood he didn’t have and, he hoped, a chance at a decent future.

His kids came first. They would always come first.

“See?” Otis asked. “Change isn’t all bad. There’s a huge upside to this.”

“Yeah, it’s a bold new era in picking up other people’s shit,” Doug said with mock enthusiasm. He stabbed his cigarette into the ashtray on the desk. “Good night, Otis.”

Minutes later, Doug drove his truck out of the lot and onto the long road home. Snow swirled in his headlights; it was already shaping up to be a crappy winter. The roads were thick with snow, but he drove nice and slow and trusted his four-wheel drive, one hand gripping the steering wheel and the other rooting for his lighter in the breast pocket of his flannel shirt. The orange glow of the sodium streetlights marked the way home. Leo Boon, his favorite country and bluegrass singer, crowed on the truck’s CD player: The buck stops here. Yes, sir.

Otis had accused him of always thinking the world was out to get him, but it really did seem that way sometimes. Nobody was looking out for Doug, that was for damn certain, and he sure as hell was the only guy looking out for his family.

The truck rattled as he picked up speed. He glanced at his speedometer; sure enough, it read a little over forty-five. His pickup needed an alignment, another hundred twenty bucks he didn’t have. He tapped the brake with his foot until things stabilized. An old rage burned in Doug’s chest. Every time he got paid, something needed fixing or replacing. His life seemed like one big race to earn as much money as he could as fast as possible to replace everything that was always breaking.

“Goddamn it,” he said quietly, still thinking about the new rigs. Damn everything. He wanted to punch something. He wanted a drink. He lit another Winston instead and counted to ten. No way he was bringing this shit home with him, not again.

Our War

Our War The Children of Red Peak

The Children of Red Peak Hara-Kiri_a novel of the Pacific War

Hara-Kiri_a novel of the Pacific War The Killing Floor

The Killing Floor The Infection

The Infection The Infection ti-1

The Infection ti-1 Silent Running: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 2)

Silent Running: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 2) Suffer the Children

Suffer the Children Crash Dive: a novel of the Pacific War

Crash Dive: a novel of the Pacific War Pandemic r-1

Pandemic r-1 Over the Hill: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 6)

Over the Hill: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 6) Battle Stations: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 3)

Battle Stations: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 3) This Is the End: The Post-Apocalyptic Box Set (7 Book Collection)

This Is the End: The Post-Apocalyptic Box Set (7 Book Collection) Hara-Kiri

Hara-Kiri Hara-Kiri: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 5)

Hara-Kiri: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 5) Contact!: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 4)

Contact!: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 4) Tooth And Nail

Tooth And Nail One of Us

One of Us