- Home

- Craig DiLouie

Our War Page 11

Our War Read online

Page 11

She handed over her copy. “It’s not mine.”

He rubbed his hands for warmth before accepting it. Her editor had been a handsome man before the war thinned him out and ground him down. He wore an eye patch, the result of taking a club to the face during the street fighting in the early days of the troubles.

“So what happened?” he said.

Aubrey sat in one of his visitor chairs and gestured to the papers. “It’s all there. UNICEF, and another story about a sniper shooting.”

He started reading. “You’ve been a busy beaver.”

Days of running, two hours of typing. A reporter devoted very little time to writing. She spent most of her time finding the story and sticking with it. Being at the right place at the right time, as close as possible to the action.

That’s how Eckert ended up with fuzzy vision in one eye and she almost ate a bullet on Meridian. Journalism was now a hazardous profession in the USA.

“Oh, I have something else for you.” She reached into her backpack and tossed a carton of Marlboros onto his desk. “Courtesy of our friends at the UN. A thank-you gift for forcing one of your peons to act as their fixer.”

Eckert blinked and snatched it up, her copy forgotten. He ran it under his nose as if he could smell the sweet tobacco through the packaging. “See this, my friend? This is how you butter up an editor. Watch and learn.”

“I’m happy I won’t have to smell those lousy roll-ups you’ve been smoking.”

Eckert tore the carton open like a Christmas present. The packs spilled out. He picked one up and unwrapped it with glee.

“Look at you,” she said. “Why don’t you quit while you’re alive?”

“Because then I’d start drinking again.”

The editor lit up in violation of a building regulation nobody cared about anymore. Like the medical professions, Indy’s psychologists worked nonstop to serve Indy’s population of walking wounded. Everybody was a bag of nervous tics, suppressed memories, and raw need. For Eckert, smoking got him through the day. He made it look good. Aubrey knew better than to try one, though. She’d get hooked in an instant, and it was a habit she couldn’t afford.

“After you’re done reading, I’ve got two more ideas in the pipeline,” she said.

“You’re going to have one hell of a resume when this is all over.”

That wasn’t why she worked so hard. The job was her bad habit. Her fix.

“Not that I—”

She stopped. Eckert was reading. He produced his dreaded red pen and started marking up her copy, shaking his head.

“And the word its doesn’t always have an apostrophe,” he said. “Overall, this UNICEF story is pretty solid. What’s she like? This Gabrielle Justine?”

Aubrey flashed to the UNICEF worker at the clinic, quaking with rage as she demanded information about the use of children in the war. “Competent. Fragile. Totally hot. You’d fall in love with her.”

“It’s a war. I fall in love with everybody.”

Eckert started in on her next story about the sniper shooting. His smile, left over from his witty remark, evaporated as he read.

He finished his cigarette and ground it out in his ashtray. “I can’t run this.”

She’d written eight hundred words on what it was like to see the bullet strike the person next to you instead of you. “I know it’s not my usual—”

“‘The main thing that held America together so long was common ideals,’” he read aloud. “‘Equality and opportunity. Democratic government. The Constitution. Without them, America is just another multiethnic empire. A bunch of tribes. In the past decade, environmental depletion and income inequality created scarcity and hardship. For many, America stopped delivering on its ideals. Instead of solving these problems, we retreated into tribalism. Fed by alternate news sources, we ended up living in divergent realities and different stories. Competing ideas of what America is about. Marsh’s election was a symptom, not the disease. Two Americas, but if Zoey was right, maybe more. Maybe many more. The war awakened something primal in us. The war may end, but we may never come together again unless we rediscover that unifying idea of what America is.’”

He set it down. “It’s compelling, but it ain’t news.”

“We run tons of opinion and analysis.”

“Yeah, from experts. People who spent their whole life studying politics. I have expert analysis coming out my ass. What people need are facts, and what I’m lacking is trained reporters. I need you to deliver facts.”

“Sometimes, it works best to tell people’s stories,” Aubrey said. “That’s how you make the reader care. One person’s story can tell the story of an entire war.”

“You can do that while remaining objective,” he told her. “We’re called the fourth estate because we’re the fly on the wall. You made yourself the story in this piece. You went through a horrific experience and needed to purge it. I’ve got reporters who want to turn my newspaper into their diary.”

He handed back the story. “Give me facts I can print. You said you have two other stories on the go. What else have you got?”

“For one, newsflash: You’re an asshole.”

He shrugged. “Noted.”

Aubrey told him about the Peace Office’s work and her visit to the clinic in Haughville, where she saw child soldiers.

“Child soldiers,” Eckert said. “In America. Sweet baby Jesus. Give that one everything you’ve got.”

“I’m not sure how much I can give it. I’m on UNICEF’s agenda.”

“And the hot UNICEF lady has a car and gas, right? Put two and two together. Run over two birds. Just make sure you get both sides.”

“Both sides?”

“Yeah,” he grated. “That’s what reporters do. They cover both sides. See if you can get any rebels to talk to you. Work your contacts.”

Aubrey sat back. Eckert’s request was like asking her to seek out the sniper who’d almost killed her and question him about his attempt on her life. “You know how they feel about the press. And African Americans. Anybody who doesn’t look and think exactly like them.”

The rebel factions broke down into White supremacist blood-and-soil types, religious zealots, Ayn Randians, and patriots. None of them liked her.

“If we run a story on child soldiers in Indy, the president’s media will make hay out of it,” the editor explained. “We need to show this is an American problem. Figure out a way to get somebody on the other side to talk. Make it work. We do this thing right, it could change things. As for the story, it could get syndicated. It might even get Pulitzer interest.”

The Pulitzer Prize, the reporter’s holy grail.

Aubrey tried to suppress a wide smile but was only partly successful. “I’ll see what I can do. In the meantime, you keep this to yourself.”

“Scout’s honor.”

She pursed her lips to show him what she thought of his honor.

He lit another Marlboro and smiled. “The reporter isn’t the story, but the story is always the reporter. What the reporter wants, and how far she’ll go to get it.”

TWENTY-ONE

Across the street, a line of derelict houses terminated at a looted store called Global Liquors. Automatic weapons fire had shattered its windows and pockmarked its walls. The squad dashed across the grimy snow and found cover behind the building. Alex followed, his head swirling.

For months, he’d eaten Second Platoon’s crap. All the hazing had a point, which was to force him to man up. Pain is your friend, the militiamen liked to tell him. Mitch would have called Mom and Dad’s loving parenting part of the pussification of America, where everybody won a participation trophy without having earned anything.

Mostly, however, Alex found the hazing pointless and mean. To survive, he’d learned to read everybody’s mood, especially the sergeants, and in particular Shook, who was like hanging around a violent and alcoholic cousin.

He’d thought Mitch sticking up for him before th

e patrol had more to do with bad blood between him and Shook more than anything else, but now he was starting to think it was because Mitch looked after his own. The way the guys talked to Alex back at the staging point clinched it. They’d never talked to him like that before.

He’d graduated to the bottom of a much smaller totem pole.

The soldiers ahead of him leapfrogged up the alley. Whatever they’d been before, they’d found a higher purpose here, fighting their civil war with a mix of conviction and cosplay. Alex suddenly regarded them with something like kinship. He still didn’t buy into everything they talked about—the globalist Marxist cabal, Agenda 21, the global warming hoax, the New World Order, and the rest of it. He didn’t even understand half of it. But he’d try to believe, if only to belong.

He certainly looked the part now. He wore a six-point light assault rig over his camouflage jacket. His rifle attached to it using a tactical sling, which helped ensure steady and accurate shooting. The webbed harness held five magazines, a canteen, and a radio.

In short, he looked pretty badass, though the only people around to admire him were guys dressed just like him. Janice Brewer, his old crush back in Sterling, might as well have been on the moon.

The militiamen raised fists as a halt order passed down the line. Alex turned to see if anybody was sneaking up on him. Nobody there. By the time he turned back, the squad was moving again, fire team A bounding while B provided security.

No contacts so far. Mitch said today’s patrol was a practice run to probe the Indy 300’s line. In three days, they’d be doing it for real. A big offensive, maybe the last—

Gunfire rent the air.

Alex dove behind a dumpster. His bowels liquefying, he peered out. His squad had melted into the scenery. The firing built to a steady roar. Bullets ripped past him. He gawked at it all, mesmerized.

Holy crap, it was so cool. Like being in a movie.

Men shouted over his radio. Mitch gave orders. Jack darted across the alley and disappeared. The squad was spreading out to probe the enemy line.

Rounds pinged off Alex’s dumpster. He ducked back behind it laughing, amped up and breathing hard. That’s why these guys did it. Now he understood. It was all a big game. Every sense tingled, fully alive. A whole different kind of high.

He wished the libs would come test him. He went prone and peered out again at the empty alley. Muzzle flashes winked in the distance. The air had gone hazy with smoke. Alex aimed down his barrel using iron sights and squeezed off a few bursts, whooping.

He barely had any idea what he was firing at. In the movies, the hero always saw who he was shooting, but this was real. Mitch called it fire superiority. Throw enough bullets at the enemy so they can’t shoot back.

Voices on the radio. Any moment, the squad would break contact and call it a day. All Alex had to do was keep his eyes peeled so they didn’t get flanked.

He sat up with a jolt. He was supposed to be watching their six.

When he turned, he spotted a Black man carrying a big hunting rifle. Indy 300.

The man was sprinting right at him.

Alex watched dumbly as his brain struggled to process it. Then alarm shot through him like electric current.

The man was coming to kill him.

Fight or flight. Nowhere to run. They raised their weapons at the same time.

The guy was shouting at him in a strong, loud voice. Alex yelled back at him to surrender, but the words caught in his throat and came out in a weak, high-pitched whine. He was shaking now, unsure he could even shoot.

Time stretched into eternity.

He started to raise his hands in surrender. The man stepped back at the sudden movement, his rifle discharging with a heart-stopping bang. Alex flinched. The bullet cracked against the dumpster and whirred away.

He was already firing back as if his gun had a mind of its own. The rifle snarled and jolted in his grip. He found his voice in a scream as he held down the trigger and drained the magazine in seconds.

The man turned to run. Red mist puffed from his back. He spun like a top as the bullets tore into him. The rifle flew from his hands. He hit the snow hard.

Eternity collapsed into a single instant.

Alex frantically patted his body looking for a wound. He was okay. The Indy 300 fighter lay spread-eagled. With an anguished moan, Alex staggered toward his victim, oblivious to the firefight still going on in the alley.

He fell to his knees. The man gaped back at him, face twisted in a wide-eyed grimace of pain and terror. His jacket had smoking holes in it. The force of the shots had knocked his hat off. Blood spray colored the snow.

“I’m sorry,” Alex said. “I’m really sorry.”

The enemy fighter gasped for air. Rapid, shallow breaths.

Footsteps pounded behind him.

Jack yanked his tube mask down, breathing clouds of vapor. “Holy crap, Alex.”

“I didn’t mean it! He shot at me.”

“Yeah.” The kid stared at the dying man. “I hear you.”

More footsteps behind. Tom shouldered Alex out of the way. He pulled out his med kit and pressed wads of gauze against the wounds.

Mitch approached. “We got hostiles on our six. Keep it moving.”

“This man needs our help,” Alex said.

“His people will take care of him.”

Tom stood. “He’s gone.”

Alex stepped back. The world swam in his eyes. He couldn’t stop shaking. “I didn’t mean to. I didn’t. I’m really sorry.”

Mitch gripped his shoulder. “You did good.”

“He shot at me first!”

“Whatever you’re feeling, save it for later. We have to move out.”

Whatever he was feeling.

Relief. Accomplishment. Sadness.

A terrifying sense that it had been way too easy to shoot a human being.

That this wasn’t a game after all.

Grady smiled. “We tell the kid we’ll get him laid if he shoots a lib, and look what he does.”

“Shut up, Grady,” Tom said.

“I was just saying—”

“Say another word and I’ll knock you flat.” Mitch’s eyes bored into Alex’s. “You’re all right, kid. We’re moving out now. Got it?”

Alex shuddered. “Okay. Yeah. I’m good.”

The men nodded at him before running off one by one. Jack lingered a moment to pat his back in sympathy or approval or both.

Alex was one of them now. He’d earned their respect.

He wondered if gaining it was worth losing his own.

TWENTY-TWO

Streetlights across Mile Square winked on to emit a weak glow. Aubrey pedaled faster, not wanting to miss out on the daily ration of electricity. Most of the city’s juice went to keep essential services going. In the evening, however, everybody got to use it for a short time.

Along the way home, she thought about the impossible task Eckert had given her. The impossible question he wanted her to ask Gabrielle Justine. She was sitting on a big story, a story that could have a real impact. She had it all to herself. But first she had to confirm whether the rebels were also using child soldiers.

Which might get her killed.

The Reds regularly targeted the mainstream press, which they regarded as part of their pantheon of liberal evils. To many of them, anything to the left of Fox News was Marxist propaganda. In their minds, people like her had started the war by turning the public against President Marsh.

In the early days of the troubles, every network covered the massive Occupy protest at the National Mall in Washington. Just before masked gunmen began shooting into the crowd, they targeted the journalists first. One by one, the camera feeds covering the protest died. They’d been shooting at the press ever since.

It was hard to be objective when one of the sides in the conflict you were covering considered you a combatant and wanted you dead. People who would put you in prison or against a wall if they won the war.

/>

The usual armed guard stood watch in the building lobby. He let Aubrey pass and went back to stomping his feet to keep warm. She hauled her bike up the stairs. The third-floor hallway was smoky and smelled like boiled food and waste.

Back in her apartment, she turned on a single table lamp and plugged in her cell phone and laptop to charge. She opened her music app and started a classical playlist. There was something about war that made her yearn for traditional forms, which she now found soothing, almost spiritual.

The Spartacus overture washed over her. It sounded like civilization. A reminder of humanity’s incredible capacity for beauty amid so much savagery.

Aubrey went through the day in professional denial of the horrors surrounding her. Earlier, she’d watched a doctor saw off a man’s foot in a clinic filled with misery. A pregnant girl’s head exploded right in front of her. It was only now, in the privacy of her apartment with her music, she allowed herself to strip away her armor and process it all.

She stood weeping with her back to the wall. That poor girl, she thought. That poor stupid girl who thought she could change the world. Murdered in broad daylight on a busy street.

Once, that would have been big news, but the war had reduced individual tragedy to the mundane. Dog bites man wasn’t news while man bites dog was, but everybody was biting dogs these days. Now if fifty Zoey Tappers had been killed in a single attack, maybe a hundred…

She caught herself with a start and checked her watch. She barely had enough time to prepare and eat her dinner. She forced her feelings aside like Pandora in reverse, putting all the world’s evils back in their box.

Aubrey lived in her kitchen now, which was away from the front windows, their fragile panes crisscrossed with electrical tape. She’d seen what flying glass did to the human face. The rebels didn’t have artillery, but the First Angels had two mortars they liked to fire randomly at the city and airport. They were evangelicals who believed if there wasn’t a God, humans would go on a rampage of murder and rape. It turned out it wasn’t God holding them back but the police and laws everybody once agreed to obey, laws the war was busy rewriting.

Our War

Our War The Children of Red Peak

The Children of Red Peak Hara-Kiri_a novel of the Pacific War

Hara-Kiri_a novel of the Pacific War The Killing Floor

The Killing Floor The Infection

The Infection The Infection ti-1

The Infection ti-1 Silent Running: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 2)

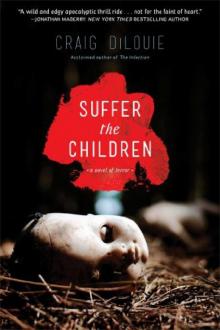

Silent Running: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 2) Suffer the Children

Suffer the Children Crash Dive: a novel of the Pacific War

Crash Dive: a novel of the Pacific War Pandemic r-1

Pandemic r-1 Over the Hill: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 6)

Over the Hill: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 6) Battle Stations: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 3)

Battle Stations: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 3) This Is the End: The Post-Apocalyptic Box Set (7 Book Collection)

This Is the End: The Post-Apocalyptic Box Set (7 Book Collection) Hara-Kiri

Hara-Kiri Hara-Kiri: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 5)

Hara-Kiri: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 5) Contact!: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 4)

Contact!: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 4) Tooth And Nail

Tooth And Nail One of Us

One of Us