- Home

- Craig DiLouie

Silent Running: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 2) Page 11

Silent Running: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 2) Read online

Page 11

“Have you started a plot?”

“I was waiting on the captain. Is he coming?”

“Start a plot, Miller.”

“Aye, aye!”

Charlie stepped back from the periscope, feeling jittery. The radar contact had gotten his blood up, but he had nowhere to expend his energy. “Down scope.”

“Sound, Control,” the soundman reported. “Uh, I think that’s Yosai.”

Yosai!

Charlie fought to keep his voice steady. “What makes you say that?”

“He’s got a signature. One of his propeller blades is bent.”

When fighting underwater, a submarine listened using sonar and hydrophones. Sonar emitted a loud ping that gave away location, typically a no-go for a warship whose primary advantage was stealth and surprise. The hydrophones, attached to the hull, picked up noise in the water, and it did it passively.

Propellers made noise. Specifically, resonation, plus cavitation caused by air bubbles forming on the blades as they cut through the water. Different sizes of screws, and how fast they turned, produced characteristic sounds. A well-trained and experienced soundman could distinguish one set of screws among others and make an educated estimate of the target’s size, bearing, and speed.

Charlie grabbed the microphone and keyed the 1MC. “Attention, all hands. This is Lieutenant Harrison. Lieutenant-Commander Hunter is unable to perform his duties due to illness. I have assumed command. That is all.”

No need to elaborate on the nature of the illness. The crew would likely think the captain was on a bender again. Let them. Doc and Jane would spread the word about the meningitis outbreak. He didn’t want to start a panic if he was going to—

Going to what?

Was he really considering taking on a heavily defended aircraft carrier?

Two heavy cruisers. Six destroyers. Up to 200 depth charges.

Yosai, the Fortress, had been aptly named.

Yet he really, really wanted to sink the bastard.

Ensign Miller stared at him with his mouth open, probably wondering if he was going to declare battle stations and initiate the approach.

Think before you act, Charlie reminded himself.

He closed his eyes and performed a series of mental calculations. The calculations became a picture in his mind. The picture became a plan.

He said, “All compartments, prepare to surface. Forward engine room, secure ventilation. All compartments, shut the bulkhead flappers.”

The telephone talker relayed the orders and reported, “All compartments report ready to surface in every respect, Mr. Harrison.”

“Very well. Surface.”

The alarm blared. The manifoldmen blew the main ballast tanks.

Sabertooth angled up and broke the surface of the sea.

“Helm, come left to one-seven-oh,” Charlie said. “All ahead full.”

“Come left to one-seven-oh, aye,” the helmsman answered. “All ahead full.”

“Radar, Control. Sugar Jig, make an automatic sweep on the PPI.”

The SJ radar swept the surface, revealing a new set of pips on the plan position indicator screen. The radarman reported Yosai’s current position.

“Steady as she goes,” Charlie said. “Bryant and Liebold to Control.”

Gibson relayed his request over the 1MC. In moments, the officers arrived and joined him at the plotting table.

“What’s all the ruckus?” Bryant wondered.

“Gentlemen,” Charlie said, “we’ve located Yosai again.”

“And we’re steering well clear of her?” Liebold guessed with a note of hope.

Charlie tapped the plot. “The carrier group is here, moving at a speed of twenty-five knots. We’re here, moving roughly parallel to them, at eighteen knots. Before they can pass us, we’ll come right here and submerge in their track.”

“I’d sure love to drill some holes in Yosai,” Bryant said. “But we took heavy damage last time we fought him. I’m not sure our boat is up for another fight.”

He was right, but the boat’s essential systems had survived largely unscathed. Engines, battery, propellers, and torpedo tubes. Sabertooth could operate in combat. She just might not survive another depth charging like the last one.

“Are you seriously thinking about taking civilians into a fight against an aircraft carrier?” Liebold asked him.

Charlie grit his teeth. He hadn’t thought of that. Still, they were fighting a war. Their standing orders were to sink Japanese ships.

And there the enemy was, daring him to attack.

“Not to mention,” Liebold went on, “the fact we’ve got sick civilians, a sick captain, and no exec.”

Charlie frowned again. “You wanted to see what Sabertooth could do, didn’t you?”

“Sure, but—”

“This is how you do it, Jack. You have to take risks.”

Still plotting, Ensign Miller watched them with wide eyes.

“Pretty big risks,” Bryant muttered. “Then again, it’s a pretty big reward too.”

“Do you know how many IJN heavy carriers are in operation right now?” Charlie asked them.

“If our intelligence is right, just three,” Liebold said.

“That’s right. We sank four of their carriers at Midway. Meanwhile, all we’ve got in the theater right now is Enterprise. If we sink Yosai—”

“It could change the strategic balance in the Pacific,” Bryant said.

“It could change the war.” Charlie tapped the plot. “The boat will be in their track just before dawn. We’ll let them pass over us and surface in their wake. We’ll fire a spread up Yosai’s skirts and head north balls to the wall. If anything goes wrong, we’ll let him pass without a shot.”

The men said nothing as they chewed on that.

Charlie went on, “Any problems with the plan? Anything I’m missing? I need to be able to rely on your experience.”

He knew by now he had a penchant for being aggressive. When his blood was up, he found a way to rationalize decisive action. If he decided to attack, he wanted to consider every reason why he shouldn’t, every risk.

Bryant said, “It’s a long shot. And you heard me say the boat can’t take another pounding. But some opportunities you can’t pass up, right?”

Charlie fixed his gaze on Liebold. “What about you, Jack?”

“The safe move is to deliver these people to Darwin. Get the boat patched up and the captain to a hospital. Fight another day.”

“I didn’t sign up for this to play it safe. I signed up to kill Japs.”

Bryant guffawed. “I think I’m starting to like you, Harrison.”

“All right,” Liebold sighed. “It’s your call. I hope you know what you’re doing.”

“That’s what I’m trying to figure out,” Charlie told him. “Is there anything I’m missing?”

“Yeah. If we’re going to sink a carrier, the torpedoes we shoot have to work.”

Charlie said, “Bryant, take the con. Jack and I are going to the forward torpedo room.”

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE

DAMN THE TORPEDOES

The forward torpedo compartment was the largest aboard the Tambor-class submarine. Currently, it was manned by six sailors and occupied by several mothers and a gaggle of screaming children who touched everything in sight.

Twelve torpedoes, one in each forward tube and another six stacked in rows, filled most of the room. Four skids, emptied during the failed attack on Yosai, now served as bunks for the refugees. Pipes, valves, and gauges crowded the rest of the space.

During action, Torpedoman First Class Freddie Kemper oversaw the operation. Two sailors manned the tubes, responsible for opening and closing the inner and outer doors. They also operated the manifold, which kept the boat balanced every time a one-and-a-half-ton torpedo blew out into the sea. A man checked the angle set on each torpedo’s gyroscope. Another worked a manual firing key in case the torpedo didn’t respond to the electrical firing

command from Control. The reload crew swung fresh torpedoes into position using chains.

In combat, they worked together like a machine.

“Why are we here?” Liebold asked him.

“We’re here,” Charlie said, “because I want you to fix the torpedoes.”

Liebold sagged. “That’s what I thought. You know it’s against Bureau of Ordnance regulations to mess with these things.”

“I do know that.”

“We could wind up in front of a court martial for this. You’re talking about messing around with a 10,000-dollar piece of government property.”

“Any other objections?”

“I could screw up and blow us all to hell?”

Charlie remembered something Reynolds had asked him back on the 55. “How bad do you want to kill Japs?”

He’d already answered that question for himself. He wanted to sink Yosai so badly he was willing to risk his career, not to mention their lives.

“That’s not a fair question, Charlie. This is reckless.”

“No,” he said. “What’s reckless is going into combat with torpedoes that don’t work. It practically did the Old Man in. It almost did us in.”

Liebold squinted at him, no doubt trying to figure out whether Charlie was the fearless hero he’d initially thought he was, or simply a madman who’d gotten lucky and ended up being called a hero for it.

Charlie decided to try another angle. “Look. If we don’t get a clean shot at Yosai, we’re not going to use the torpedoes. I’ll report the modification when we reach Darwin. I’ll take full responsibility.”

“All right, Charlie,” the officer said. “I’ll modify the torpedoes.”

“Good.”

“On your orders,” Liebold added.

“I’ll take what I can get. Show me what you think we can do.”

Liebold asked Kemper for a set of tools. He removed the plate from the firing controls of one of the big Mark 14 torpedoes. Kemper watched him work with mounting alarm.

The Mark 14 carried a warhead containing close to 700 pounds of Torpex, a compound more explosive than TNT.

Charlie looked inside and inspected the sophisticated firing mechanism. It must have weighed a hundred pounds on its own.

“The Mark 14 uses the Mark 6 magnetic pistol exploder,” Liebold explained. “It’s based on a simple compass. When the needle swings toward an enemy ship’s magnetic field, the firing pin is released.”

The older contact exploders were proven but had a significant disadvantage. Even with the higher level of explosives packed into the Mark 14, it might not be powerful enough to break the hull of a heavily armored battleship. Under the keel, though, the battleship was vulnerable.

That was the idea behind the Mark 6 magnetic exploder design. The Mark 14 swam under the warship and came into contact with its magnetic field under its keel, or bottom. Then it exploded, breaking the ship’s back. In theory, anyway.

“So the torpedo doesn’t explode before you want it to, the warhead stays unarmed for 450 yards,” Liebold said. “It uses a spinner activated by the torpedo’s movement through the water.”

The problem was the torpedoes often went off prematurely at 450 yards.

Some of the braver kids edged in closer to stare at the gadgets and wiring packed inside the torpedo. Kemper shooed them away.

“And here,” Liebold said, “is the anti-countermining mechanism. It keeps the firing pin from moving and accidentally blowing up when the torpedo gets near an explosion, mine, or other torpedo.”

“All right,” Charlie said. “So you said there are three problems with the Mark 14. First, it goes off too soon.”

“That’s right. I’d have to take out the Mark 6 exploder and put in a contact exploder. I may also remove the anti-countermining just in case that’s the problem.”

After that, the torpedo would arm at 450 yards and explode only when it touched the hull.

“Good. The second thing is it travels too deep.”

Submariners were very concerned with a ship’s draft, which was the distance between the waterline and the keel. A typical Japanese ship’s draft was fifteen to thirty feet, depending on how heavy it was and whether it was loaded.

During an attack, a submarine skipper usually set torpedo depth at around ten to fifteen feet if he wanted to hit the target under the waterline, close to the keel, and put a hole in him. Water then poured into the ship, and it sank. A simple formula.

“How did they come up with the depth setting?” Charlie asked.

“The Bureau tested them.”

“Were the test torpedoes any different than what we have?”

Liebold smiled. Then he laughed. “That’s a very good question. I have a guess. The idiots might have tested the fish with dummy warheads. The real thing could be a lot heavier. That weight makes them run deeper.”

“Any way to fix it?”

“Set the depth shallow, maybe at four feet, and hope for the best.”

Liebold believed the torpedoes were running ten to fifteen feet deeper than their setting, but he could be wrong. If the torpedoes ran true at four feet, there was a risk of one or more broaching or getting thrown off course by the waves.

Charlie would have to gamble that Liebold was right. The man’s solution wasn’t ideal, but it was the best they could do. They couldn’t test the modified torpedoes themselves. They’d have to take the chance.

“That just leaves the problem with the fish failing to detonate if they hit the target dead on,” Charlie said. “Any ideas?”

“I don’t know. All I know is square shots often don’t explode.”

Kemper chimed in, “The firing pin might be jamming on impact, sir. Try hitting the target at an oblique angle.”

Charlie grinned to hide his anxiety over the number of unknowns. “Thanks, Freddie. Jack, make the modifications you need to make, and if we get a clean shot at Yosai, we’ll put them to the test. Make lemonade out of these lemons.”

“You know, everything I’m saying is just a theory. Other captains have tried just what you’re saying, and the torpedoes still didn’t work. There might be a manufacturing or design flaw we don’t know about.”

“From what you told me, nobody else connected the dots and tried all three remedies at the same time. Am I right about that?”

“I haven’t heard anybody trying it,” Liebold replied glumly. “No.”

“Don’t look so down about it, Jack. If this works, it could do a lot of good.”

“As long as you know that a lot of men who try to do the right thing get booted out of the Navy. If I don’t blow us up first. And you know, there’s another possibility here. Which is the torpedoes work great, and the captains simply missed.”

Charlie ignored all that. “How long until you can get all the fish modified?”

“Ten hours, maybe, to do them all.” He caught Charlie’s frown and shrugged. “If you want it done, that’s what it’ll take.”

“Do what you can. Send me a message every time a torpedo modification is completed. I want six modified torpedoes in the bow tubes, ready to fire. Then do the ones aft. We might need them to cover our escape. Can you do all that?”

“Aye, aye,” the man said. “As in I’ll do my best.”

“I’ll help out,” Kemper said. “Make sure we don’t all get blown to hell.”

“Do this right, Jack, and we’ll sink one of the IJN’s biggest warships.”

“Either way,” Liebold said, “I hope you understand I think you’re dangerous.”

Charlie could live with that.

Lt. Charlie Harrison’s plan to attack the IJN aircraft carrier Yosai in the Celebes Sea, December 21, 1942.

CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX

SECOND GUESSES

Midnight. Charlie had his dinner in his cabin, listening to the captain moan in his sleep across the way. No help there. Charlie was on his own.

Aside from the plotting party, the crew was at relaxed battle stations. In t

wo hours, he’d call them to battle stations and begin the final approach. In five hours, they’d submerge in the carrier battle group’s track and attack.

He had the mettle to go through with it, of that he was certain. But Jack Liebold’s and Rusty Grady’s judgment of him planted seeds of doubt. Liebold said he was dangerous. Rusty once told him he had a death wish.

Was it true?

He’d learned how to be a good captain from J.R. Kane—and to an extent from Bob Hunter.

Kane, the chess player: You wait for your move and then act decisively.

Hunter, the Hearts player: You make your own luck through good planning.

But maybe he was more like Reynolds, the 55’s brooding exec, who had no use for games. You ask yourself how bad you want to win, and then you attack, attack, attack. You fight like you’re already dead.

Maybe that was the real him. Lewis had told him buccaneering wasn’t allowed on Sabertooth, but Charlie suspected he was a buccaneer through and through.

“Buccaneer” wasn’t necessarily a bad word. Buccaneering achieved great victories. But it also got good men killed. And not just men who’d volunteered for this hard life and its risks. Charlie had twenty-one civilians, including women and children, in his care. He was responsible for their welfare.

The problem with decision and action is sometimes long hours separated the two. Millions of chances to make a different decision.

He thought he should try to catch some sleep, but he knew he couldn’t. He forced down the last of his coffee and went to the wardroom.

Tended by the pretty nurses and the pharmacist’s mate, four men and two children lay on the floor. The chief of the boat stood guard at the door. One of the kids arched her back and let out an alarming scream. The phonograph played Bing Crosby crooning, “Lullaby.”

“Jane,” he said. “How’s it going?”

“Honestly?” She pulled down her mask and sighed. “It’s going pretty bad, Charlie. We’ve got six here laid up along with the captain, all down with the bug.” She gestured to the passageway. “Out there, infected but not yet symptomatic, who knows? Could be two, three times that. I hope you’ve been washing your hands.”

Our War

Our War The Children of Red Peak

The Children of Red Peak Hara-Kiri_a novel of the Pacific War

Hara-Kiri_a novel of the Pacific War The Killing Floor

The Killing Floor The Infection

The Infection The Infection ti-1

The Infection ti-1 Silent Running: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 2)

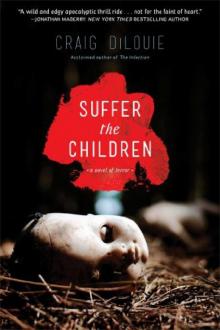

Silent Running: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 2) Suffer the Children

Suffer the Children Crash Dive: a novel of the Pacific War

Crash Dive: a novel of the Pacific War Pandemic r-1

Pandemic r-1 Over the Hill: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 6)

Over the Hill: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 6) Battle Stations: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 3)

Battle Stations: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 3) This Is the End: The Post-Apocalyptic Box Set (7 Book Collection)

This Is the End: The Post-Apocalyptic Box Set (7 Book Collection) Hara-Kiri

Hara-Kiri Hara-Kiri: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 5)

Hara-Kiri: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 5) Contact!: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 4)

Contact!: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 4) Tooth And Nail

Tooth And Nail One of Us

One of Us