- Home

- Craig DiLouie

The Killing Floor Page 11

The Killing Floor Read online

Page 11

♦

Shucking his Army surplus backpack heavy with cans and bottles, Ray tramps through a garden eating raw peas and any tomatoes spared by the insects. Unable to eat more, he stuffs his cheek full of Copenhagen dip and lets out a satisfied sigh. He has twenty miles to walk, which will take him two, maybe three days in his condition and carrying the weight of the pack on his shoulders. Climbing over a barbed wire fence, he angles west and starts marching through the trees, knowing Route 22 is about a hundred yards on his left. At the base of an old sawtooth oak, he picks up a good walking stick, a long wizardly staff that helps him find a steady hiking rhythm.

As the sun falls toward the horizon, his eyes roam the landscape, searching for shelter. Wind rustles through the branches and the atmosphere feels moist against his skin. The sun drops behind western rain clouds, dimming air already darkened by the forest canopy, and Ray quickens his pace as a few random drops splat on the rim of his STEELERS hat. He emerges from the trees onto a grassy field covered with a riot of dandelions. At the other end of the field, a farmhouse stands quiet, its windows boarded up, three rotting bodies drawing flies on the porch steps. A tire swing sways from the stoutest branch of a massive oak tree.

He pauses here, listening to the buzz of insects in the tall grass. The world is so lush and beautiful it is sometimes hard to believe it is coming to an end. Then he remembers the world is not ending, just its dominant species.

The sky continues to blacken. Moist wind strikes Ray in the face, carrying a few drops of rain, and he opens his arms to it. The air feels electric. The clouds rumble with distant thunder, a melancholy sound. He takes a deep breath and decides to try the barn to ride out both the night and the rain. The house appears occupied and dangerous. Get too close to that place, he might get a lungful of buckshot, looking the way he does right now. He studies his hands—workman’s hands, hairy and powerful—and realizes his survival and recovery from Infection is not a get-out-of-jail-free card. He might have to fight again, and kill again, if he wants to make it home alive. Ray has a lot for which he wants to live. Nothing ambitious, just a deep, abiding appreciation for breathing in and out. When he thinks about his fever over the past few days—weeks?—it terrifies him because he remembers little of it. He dreamed; many of the dreams were horrible. But mostly, just darkness. Trying to remember those long days of nothing is like trying to remember the time before he was born.

Rain pelts the roof as he enters the barn. Rats flee squealing from his advance, melting into the dark spaces. The building has a rich smell of farm animals and hay and old dung, but the smell is stale, a memory; the animals are long gone, the hay is rotting. Ray sniffs the air again just to be sure, but detects no sour milk stench, the calling card of the Infected. Something crunches and scatters under his boots, and he looks down, only to wish he hadn’t; the floor is strewn with little piles of bones and children’s clothes. Bloodstains have turned the dirt floor the color of rust. The barn was a nest, then; a pack of the Infected killed here, ate here, slept here, but they moved on long ago. Ray waves away a small cloud of buzzing flies and thinks about burying the bones, but he is tired and it is getting late.

“Sorry,” he grumbles, spitting a stream of tobacco juice into the dust. Ray feels like an empty husk. Something in him died when the bug took him. Or maybe he was reborn, and is still finding out who he is. Either way, he has no fight in him anymore.

He climbs a ladder leading to the hayloft, pulls it up after him, and spreads out his old rolled-up blanket on a bed of moldy hay. He pulls off his boots and then his socks and sighs with relief despite the stink, wiggling his toes. Fishing in his pocket, he finds a couple of Band-Aids and applies them over the blisters on his heels. Minutes later, he falls into a deep, blissful sleep to the soothing sound of rain pattering on the roof. Mosquitoes feast on his blood during the night.

The next morning, Ray pisses hard into the hay, smokes a stale cigarette, and cuts open a can of cold SpaghettiO’s pasta, which he eats with a plastic spoon. The air is warm and humid; his body is already slick with sweat. His legs are sore and a part of him wants to sleep the day away again. He stares into space scratching at his bug bites until boredom drives him back down the ladder and into the farmer’s yard. Beyond, winter wheat stands hunched and wet under a dim, heavy mist that shrouds the distant fields and woodlands.

He decides he likes the mist. The mist could be his friend. As long as it lasts, he can hide in it. The house still stands quiet, but Ray is certain he is being watched. He feels a sudden urge to wave, or better yet flip them the bird, but doesn’t have the energy for it.

Shouldering his pack and gripping his walking staff, he disappears into the treeline.

♦

Minutes later, the mist surrounds him like a living thing. It feels cool and wet in his lungs. He cannot see more than a few feet in front of him but has the skin-crawling sensation he is still being watched. He is in danger here. Coming into the mist was a mistake, but it is too late to go back. He already no longer has a sense of where he started.

He closes his eyes and pictures sitting at a big desk in the station’s holding pen, where Unit 12, his old police unit at Camp Defiance, made its home. He and Tyler and his kid Jonesy and all the other guys in the unit, Cook and Salazar and the rest, laugh at some joke as they pass around a can of warm beer they scrounged up.

Ray just wants to go home. He does not have the stamina to live under constant threat like Anne and Todd. He needs people. He wants to be in a nice, safe place among friends.

Over time, his inability to see amplifies his hearing. Things tramp through the forest all around him. His own footfalls sound loud to his ears, as if he is walking on garbage bags filled with crumpled paper. But standing still is worse than making noise. Standing still is worst of all.

He remembers a dream he had while fighting his infection. A dream of something that happened to him when he was a kid. The dream so real, the actual memory so long ago, he wonders if it actually happened, or if he just dreamed it. In the dream, he shoved Shawn McCrea’s face into a tree while playing a trust game. That’s how he feels now, being led through the forest blinded by mist. At any moment, he is going to get sucker punched.

His father’s voice: Hey Ray, come here a minute.

Ray breaks into a run, hands splayed to ward off low-hanging branches. In his mind’s eye, his father is about to hit him. The fog is so blank it is easy to write one’s memories and worst fears onto it. He wants to outrun the old man, but, as in a dream, he cannot move. In his memory, he loves his father too much to leave, so he obeys; he walks meekly to his dad. And gets slapped. It feels good to get it over with. The worst part is the waiting. The cat and mouse game.

Leona, stay out of this or you’re next. Kid’s got to learn. He’s got to toughen up.

The sad thing is, Ray believed him. He believed his father was trying to help him when he got drunk and slapped him around for not being strong enough.

A black shape forms in the mist, coalescing into a gaunt, looming monster. Ray gasps and falls to his knees, his heart galloping in his chest.

This is it. I’m going to die.

It almost feels good to get it over with. As always, the worst part is the waiting.

It registers in his panicked brain that the monster is a tree. Ray curls up at its base, shaking with terror. It is like being back in the storage locker, trapped with his own memories and thoughts. It was his past that drove him back out into the light of day.

Ghostly voices call in the mist. The sound rakes across his already tattered nerves. A motor engine revs before cutting out. Then silence.

He feels light on his face and blinks into the fleeting glare of sunlight winking through the forest canopy above. The fog is dissipating, retreating into shreds and wisps.

The voices shout again, clearer this time.

Ray peers out from behind the tree. A Winnebago sits parked on the shoulder of the highway, a battered state police cruise

r next to it. A man with a hunting bow stands guard near two men hunched over the RV’s engine, while a woman sits behind the wheel of the police car. They look as terrified as he feels.

“Hurry up, the fog’s lifting,” the man with the bow says. He wears a tank top and fluorescent blue jogging shorts, exposing hairy, thickly muscled arms and legs.

Shaking, Ray stands, hugging the tree, and considers how to approach them. Should he call out? The alternative is to walk out there nice and calm, hands in the air. Either way, he might get one of those arrows in his ribs. They might think he’s infected. They might not be friendly to strangers.

No choice, then. He will have to call out and see if they’ll welcome him. He is starving for human company, driven by a need to be in the middle of the herd. He made it this far, but he knows any luck he’s had is running out.

Something thrashes in the foliage. Ray drops his pack and draws the steak knife. A pair of Infected, a man and a teenage girl, burst from the bushes snorting, leaves and twigs falling from their hair. Ray crouches, willing himself not to be seen, his body electrified by a shock of adrenaline. The Infected run past his tree, heads wagging, their faces and arms a ghastly patchwork of livid red scratches. The girl snarls, revealing braces black with decaying meat.

An arrow thuds into the man, who falls thrashing in the tall grass just outside the treeline, shrieking like an animal. The bowman notches another arrow and shoots the girl through the hip. She falls, gets up, then falls again, writhing and bleeding on the grass.

More Infected emerge from the woods, drawn to the sound of the cough of the Winnebago’s engine as it tries to start. The woman in the police cruiser screams when she sees them, covering her ears. The man with the bow crosses himself and gets back to work.

Another arrow whistles though the air, flying through a young woman’s throat before piercing a man behind her in the face. The man howls and runs in circles, batting at the arrow flopping around his head; the woman continues to run, coughing blood with each stride, until pitching forward into the grass.

“Right on,” Ray hisses. He feels a strange kinship with the archer wearing the ridiculous shorts. He wants to get into the fight and help. He pictures leaping from behind the tree, joining the pack of Infected running past and cutting their throats one by one with his carving knife.

Welcome, stranger, they’ll say. He and the archer will clasp hands warmly, recognizing in the other a warrior of the apocalypse. Because he helped them, they will trust him. Then they’ll get the Winnebago running and drive it to Cashtown in comfort. It’s a good plan.

The fantasy over, he does not move. He clings to the tree, feeling rooted to the spot, watching the Infected close in on the group. It’s not my fight, he decides. Not my problem. Sorry, sorry, sorry. I’m too tired. All I have is a knife some family used for carving rib roasts.

But the truth, again, is there is no fight left in him.

More Infected run across the field behind the survivors. The man with the bow sees them and fires another arrow, which misses. He shakes his head and says something to the men working on the Winnebago, who ignore him. The archer roars at them to move. The man hunched over the engine raises his head, blinking at the Infected rushing at him, and bolts for the police cruiser with the other man at his heels. The group slams the doors just as a man punches the windshield, cobwebbing it. A woman climbs onto the rear of the car, scratching at the back window with her nails as the vehicle growls its way to life.

Go, Ray wants to scream. You’re surrounded. Get out of there.

The car lurches and bangs into the man, knocking him down with a sickening crunch. The woman tumbles off the back and the car roars down the road, trailing a massive cloud of exhaust and a score of screaming Infected.

Ray waits several minutes, picks up his pack and approaches the Winnebago. He spots the problem with the engine, but lacks the tools to fix it. Inside, he finds food and water, a bucket for a sponge bath, shaving kit, and personal knickknacks. The vehicle smells like people, a comforting smell.

He decides to stay the night here. Eat, sleep, shit and maybe try to get cleaned up a little so the Camp Defiance guards don’t shoot him on sight thinking he’s one of the crazies. Ray tries the stove, and permits a brief smile. He is going to eat hot food tonight, and bathe and shave with hot water. By tomorrow, with hope, he will feel human again.

He spots a photo album and opens it. Weddings. Family vacations. Births. He smiles at these highlights of a normal life, but after a while the images become difficult to look at. A proud fisherman with a prize catch. Children building a sandcastle at some beach. An attractive woman smiling flirtatiously at the camera. The photos portray memories too painful to remember, even for a stranger. And yet whoever owned these pictures is going to regret leaving them behind.

The past haunts everyone, even the good stuff. Especially the good stuff.

♦

Ray gets an early start the next morning, setting a brisk pace with his walking stick. He stays on the highway, hoping to find other survivors, but the road is deserted.

He passes an abandoned van resting on flat tires, and peers in through a gaping hole in the windshield. Animals rustle and hiss in a pile of torn luggage and seat stuffing in the back, probably a family of racoons. The interior smells like dung. It doesn’t take long for things to fall apart, Ray realizes. By the time we’re all dead, most of what we’ve built will crumble into dust.

He returns to the road, scanning the trees on both sides for ambush, but he’s not used to living so close to fight or flight, and zones out, thinking about everything and nothing. For some reason, his thoughts turn to Lola Rivera. He dreamed about her while he fought Infection, he remembers. He dreamed his entire life, it seems. It would be nice to believe some kindly force made this happen to teach him something about his life so he would make the most of this second chance, but the memories had a forced quality about them, as if they were being taken from him. Ray woke up feeling exhausted, docile, violated. All of the fight was sucked out of him. I don’t want anything, he understands, and experiences the shock of this, being a man of constant need and habit, a creature of deep drives and dark urges.

Now all he wants to do is continue living. Nothing else but live. Breathe in, breathe out.

Whatever the source of the dreams, without his rage, he can only look back on his life with remorse. He regrets what he did to Lola, how he treated her. After he sucker punched Bob at the bar and made bail, he went to the hospital and told Lola he did it because he still loved her. Every day, he went, and said he’d do it all over again, just to have her back. Eventually, something in her snapped and she gave herself to him. That night, while lying beneath him on his bed, she opened her eyes and, seeing only spite written on his face, realized he did not love her. She wept until he threw her out in a fit of anger. Rage came so easily to him, the urge to lash out instead of do the right thing. It was his automatic defense against both love and shame.

You do have a second chance here, bro. Maybe when you get back to camp, you can try to make things right with a few people, if they’re still alive.

He finds the idea surprisingly appealing.

As the sun dips low in the sky, he finds the exit for Cashtown and walks off the highway, pausing to flinch at the bang of a high-powered rifle. Ray grimaces with relief. He is not far from Camp Defiance now. The rifle shot was one of the snipers in the watchtowers doing his monotonous, grisly duty.

As he gets closer to the camp, the air fills with white noise, the sound of thousands of people and vehicles punctuated by the distant pop of gunfire. The breeze delivers the faint but familiar odors of wood smoke and human waste. He breathes deep, enjoying a sudden rush of memories. Tyler in his ridiculous red suspenders, chuckling over a book, his reading glasses perched on the end of his nose. Doug Foley loading shells into his shotgun between nips of Jägermeister, getting ready for patrol. Jonesy licking his hands and slicking back his hair in front of the mirr

or, announcing he has a hot date. Boy, are they going to be surprised to see me, Ray thinks, feeling good for the first time since he woke up.

Topping the next hill, the camp spills across the horizon, a mass of densely packed buildings and tents and vehicles all shrouded in a haze from thousands of cook fires. Mountainous walls of heaped sandbags, tractor trailers and barbed wire, buttressed by watchtowers, surround the bulging mess like an old belt, keeping it from vomiting onto the neighboring smoking fields, keeping Infection out one day at a time. Ray gazes at it for several minutes, wiping away a tear. Never did this sprawling dung heap look so good to him, not even when he crawled out of the storage locker, fleeing his fears lived over days in darkness.

He spots a series of windmills churning over the southern side, near the big circus tent, the start of a power grid. When he left to blow up the Veterans Memorial Bridge at Steubenville, the windmills were just a plan championed by the do-gooders. The people must be starting to accept they’re going to be here for a while. Ray wonders again how long he has been gone, decides he doesn’t care. The camp is still here; that’s all that matters.

He gasps, unable to breathe, wondering how fast he can run back into the trees. A man stands rock still fifty yards down the road, dressed in a ridiculous Santa costume, one arm frozen in a wave. It takes him several moments to realize it’s a store mannequin, one of many dotting the no man’s land surrounding the camp as bait for the snipers. The Infected make a beeline for the color red. Ho, ho, ho, welcome to FEMAville. BANG. Splat.

In the distance, he sees a figure running toward the wall. A woman doing the hundred yard dash, hoping to get in and spread her disease. The effort strikes him as both heroic and suicidal. The echoing roar of a single rifle shot rolls across the fields. The figure spins and falls. Ray watches as the woman continues to drag her broken body along the ground, still fighting for her cause even while she bleeds into the mud. Behind the wall, life in the camp goes on as if nothing happened.

The cracked road plunges down the hill and leads straight to the gates. All he has to do is walk down there and he’s home. But he is unsure how to get there without getting shot. It’s too dangerous to move now.

Our War

Our War The Children of Red Peak

The Children of Red Peak Hara-Kiri_a novel of the Pacific War

Hara-Kiri_a novel of the Pacific War The Killing Floor

The Killing Floor The Infection

The Infection The Infection ti-1

The Infection ti-1 Silent Running: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 2)

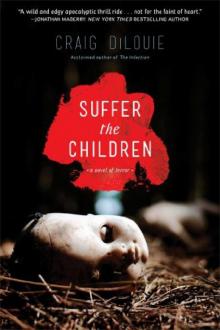

Silent Running: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 2) Suffer the Children

Suffer the Children Crash Dive: a novel of the Pacific War

Crash Dive: a novel of the Pacific War Pandemic r-1

Pandemic r-1 Over the Hill: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 6)

Over the Hill: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 6) Battle Stations: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 3)

Battle Stations: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 3) This Is the End: The Post-Apocalyptic Box Set (7 Book Collection)

This Is the End: The Post-Apocalyptic Box Set (7 Book Collection) Hara-Kiri

Hara-Kiri Hara-Kiri: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 5)

Hara-Kiri: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 5) Contact!: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 4)

Contact!: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 4) Tooth And Nail

Tooth And Nail One of Us

One of Us