- Home

- Craig DiLouie

Silent Running: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 2) Page 10

Silent Running: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 2) Read online

Page 10

Now the Old Man looked pale and shaken. He reeked of booze.

Sabertooth’s bad luck had returned with a vengeance.

Nine days, Charlie thought. We just have to hold it together for nine more days.

The sailors stood at parade rest while the burial detail carried and placed the body on a stand. Lewis’s feet protruded overboard. The men draped a U.S. flag over him.

Charlie pictured a Zeke roaring over the water, machine guns blazing, men flying apart as dozens of shells struck the deck.

But aside from the growl of the diesel engines, the night remained still. Overhead, a sea of stars.

Hunter intoned, “Unto Almighty God we commend the soul of our brother departed, and we commit his body to the deep.”

“Firing party,” Charlie said. “Present arms.”

The sailors held their Garand carbines in front of their chests. The burial detail tilted the stand. The American flag fluttered as Walt Lewis slid out from under it and struck the ocean with a splash.

“Fire!”

The guns cracked, startlingly loud. Charlie smelled gun smoke. In his mind’s eye, he saw Japanese soldiers crumple to the sand.

They hadn’t expected to die either.

Or maybe Lewis had. One way or the other, he’d forced himself out of bed to do his duty one last time. Like those soldiers, he’d died fighting.

“Fire!”

Another crash of gunfire, and then another. After the third volley, Hunter said, “Walt Lewis was a good man. He did his duty. We depended on him for our very lives, and we knew we could. It was an honor to serve with him. Sabertooth owes him a great debt. America owes him.”

Then he dismissed the hands.

Charlie listened to him cough with fresh alarm while the sailors returned below deck. Lewis was dead, and Hunter had caught something. Probably from the refugees, and likely because his boozing had wrecked his resistance to germs.

If the man could no longer perform his duties, Charlie would have to bring Sabertooth to Darwin on his own. A possibility he found terrifying even as it tempted. What he’d experienced during his brief taste of command still baffled him. That strange combination of power and pressure.

In any case, he believed nothing would happen. The captain was boozing again, something to keep an eye on. He’d caught a bug, probably no big deal.

Nine days …

Below decks, Charlie ran into a pack of children playing in the wardroom. They clustered around.

“Hey, Mister! Mom said you killed twenty Japs on Mindanao! Is that—?”

“Make a hole!” Charlie said and stomped past. The kids scattered.

He knocked on the captain’s doorframe and entered. Hunter lay sprawled out on his bunk, already sleeping it off.

Charlie sat at the desk, switched on the desk lamp, and began to read through administrative reports. As acting exec, he represented the captain in maintaining the submarine’s efficiency. It was now his job to coordinate all work done on the boat.

He pictured Lewis’s head thumping against the wardroom table. You know what your problem is, Charles?

Talk about famous last words.

God, just like that, the man was dead.

It rattled him. He shook his head and dove into his work.

The administrative reports gave him a clear picture of what was happening aboard Sabertooth. The crew had worked hard to regain good trim after offloading ninety tons and taking on riders. The submarine still carried twenty torpedoes, twelve in the forward nest and eight aft. Six men remained off-duty due to injuries they’d received during the depth charging. Tarzan remained bedridden from getting hurled against the bulkhead. Three of the refugees appeared seriously sick. Another three recovered from battle wounds sustained during action on Mindanao.

The captain snored loudly. Charlie looked over at him and thought, Keep it together, Skipper. You’re not expendable either. We happen to need you too.

He returned to the reports. The boat, he learned, suffered her own wounds. She was still leaking from damage to her hull and hydraulics. Charlie remembered the red light winking on the Christmas tree board before a recent dive, which showed whether all hull openings were secured (green) or open (red). It had taken Bryant and his auxiliarymen precious time to jury-rig a seal. Sabertooth needed a major refit once she reached Darwin. Charlie grunted as he pored over the work logs and gained a new sense of respect for the abrasive engineering officer.

The boat would make it to Australia, but Charlie doubted she had the mettle for another fight. It was probably for the best that she’d been taken over by women and children.

A knock on the doorframe. A woman’s voice: “Captain Hunter, sir? Hello?”

He sighed. Speak of the devil.

Charlie glanced at Hunter. “Captain?”

The man moaned and rolled over. He was sweating buckets, either from the booze or illness. Charlie made up his mind to fetch the pharmacist’s mate.

Right now, though, he had to deal with this visitor. He got up and whipped the curtain aside. “Yes?”

“Oh,” Jane said. “I was looking for the captain.”

She wore a man’s T-shirt and cut-off dungarees, a donation from the crew.

“He’s sleeping,” Charlie told her, keeping his voice down.

She put her hand over her chest as she caught her breath. “For such a small ship, it’s easy to get lost around here.”

“We call her a boat, ma’am.”

“And I’m called Jane. What did I tell you—?”

“Sorry. Jane.”

“Thank you, Lieutenant Harrison. That’s right. I got your name. I even heard your nickname, Hara-kiri. You’ll have to explain that to me sometime.”

Not on your life, he thought.

The captain coughed behind him.

“Can I help you with something?” he asked.

“Sorry about Lieutenant Lewis. Was he a friend?”

Charlie had to think about that. “More like a mentor. He was a good man.”

“My condolences just the same. From everybody. We’re all sorry about it.”

“Thanks, Jane. Is that what you came to see the captain about?”

“She turned scarlet. “Well.”

Charlie waited, unable to even guess what she wanted.

“It’s about the toilet,” she said finally. “It’s kind of a complicated setup.”

He smiled. “It’s probably best to let a crew member flush it.”

“I made a real mess today. We ladies use lady products, you know.”

She’d lost him again. He didn’t understand.

“Kotex, sailor,” Jane said. “We use Kotex.”

“You mean—ah.” He blushed now. “Yeah. Don’t flush that.”

“Now I know that. Thanks, Lieutenant.”

“Don’t mention it, Jane. And it’s Charlie.”

She smiled. “Okay, Charlie. One more thing. When can I get a bath?”

“You can’t. We’re rationing fresh water as it is.”

“That explains the long hair and beards,” she said. “It didn’t exactly inspire confidence when I came aboard. You all look like cavemen.”

“When we’re surfaced at night, you can take a bucket up top, tie a cord to it, and haul up some seawater for a quick sponge bath. Just be ready to run like hell and get back below deck if a lookout sounds the alarm.”

And that was a big if with girls topside. He pictured the pretty nurses washing themselves while the lookouts ogled them, ignoring their sectors. A single minute of carelessness was all it took to lose everything—the boat, their lives.

Charlie gulped. The image of the nurses washing up stuck in his mind.

“All right,” she told him. “We’ll figure a way to do that privately. Hold up a sheet or something.”

“Right,” he said, barely listening. “Yes.”

Jane lingered. Charlie became aware of little details as they grabbed his attention: her eyes, her prominent cheekbon

es, the elegant curve of her neck—

He stammered, “Was there anything else, ma’am—Jane?”

Smooth, he thought. You’re a regular Gary Cooper.

She took a deep breath. “I need to know: Are we going to make it to Darwin? Give it to me straight.”

Charlie nodded, delaying speech. “Yes. We’re going to be fine. I have to tell you, it’s not an easy thing for the boat to carry so many civilians. That’s what’s been occupying my mind, not to mention Lewis’s passing. It didn’t occur to me that you might see this trip as dangerous. It must be hard for you.”

Jane surprised him by laughing. “Are you kidding? The night before we boarded, I had my finger buried up to the knuckle in a GI’s neck.”

“Oh,” Charlie said. “Ah.” Something else he hadn’t considered—that these people had been through hell these past months. He tried to imagine fighting the Mizukaze not one horrible night, but multiple nights stretched out across months.

Jane knew war, possibly better than he did.

“Doris and Mary, they’ve been through hell,” she told him. “Some of these other folks, I’ve gotten to know them pretty good. I just wanted to hear it straight that we’re going to make it home. Thanks for telling me. I appreciate it.”

As she turned to go, Charlie heard the captain cough again. He made up his mind to ask something important. “Hey, Jane?”

“Yeah, Charlie?”

“I’m afraid the captain might have caught a bug from one of your people. Would you examine him when he wakes up?”

“Sure. Let me know when he does. I’ll come running.”

“The boat!” Hunter screamed from his rack. “We’re on fire!”

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

PLAGUE SHIP

Charlie called a meeting of the officers in the wardroom. Bryant and Liebold started at the sight of Jane, no doubt wondering what she was doing at the meeting. Holding a cup of coffee with both hands, she gazed back at them as if she owned the place.

“The pharmacist’s mate is with the captain,” Charlie explained. “He’s sick as hell. He was raving. Jane here examined him and knows what he caught. It’s bad.”

“Meningitis,” she said.

Hunter had curled into a fetal ball, shivering with his hands jammed under his armpits. Burning up with fever, sweat poured off him.

He’d smelled like sickness.

While Charlie had stood there stupidly, Jane took action. She gave the captain a quick exam and found blotchy red rashes along his neck.

“Prickly heat,” Charlie had guessed.

“Acute bacterial meningitis,” Jane told him.

In the wardroom, she explained her diagnosis and what Captain Hunter had in store for him. The disease inflamed the membranes around the brain and spinal cord. Many victims suffered fever and chills, headache, vomiting, rash, and a stiff neck. Some exhibited confusion and fear of bright light.

“Are you sure?” Bryant said. “No offense, but you’re just a nurse.”

“Excuse me,” she said. “I know what I’m doing, thank you very much.”

Liebold wrung his hands. “Is the Old Man going to be all right?”

“His odds are good. Nine out of ten pull through.”

Bryant let out a frustrated sigh. “Great news. Really. But what we really need to know right now, though, is how contagious this thing is.”

Sabertooth carried one very sick captain but also dozens of healthy people. All of them wanted to get home.

Jane said, “For people in close contact, it’s very contagious.”

“Christ.” The engineering officer lit a fresh cigarette from the wilted pack in the breast pocket of his service khakis. “We’re on a goddamn submarine.”

Which explained how the captain caught it. Charlie remembered him in the crew’s mess that first night. Hunter had shaken hands with every passenger in sight.

Now Sabertooth was looking at the possibility of an epidemic.

When they’d served together on the 55, Rusty told him about a submarine that had gone through a similar experience. A bad stomach flu that spread like wildfire. Almost every crewmember was puking his guts out and crapping into buckets.

At one point, an undefended Japanese merchant convoy steamed right past them. Focused on their survival, the crew hadn’t been able to do a thing about it. The epidemic had stopped them cold.

“It spreads easily among people living in close quarters,” Jane said. “Like army barracks. Or, yeah, a submarine. The most susceptible are young kids. Adults whose immune system is weak. The captain seems …”

She glanced at Charlie. He knew she’d seen the bottle of brandy on the captain’s desk. And she’d smelled the alcohol on his sour breath.

He gave her a blank stare. That the Old Man drank was the business of the crew and the crew alone.

Jane got the hint. “I guess your captain was just unlucky.”

“Unlucky, hell,” Bryant said. “You people brought that germ aboard. And you, a nurse! How’d you let that happen, is what I want to know!”

“Don’t look at me, mister,” Jane shot back. “I don’t know half these people. Me, Doris, and Mary, we were patching up guerillas in a hut when we heard you fellas were on your way. A lot of us met for the first time only four days ago. We spent three of those days trekking through the jungle trying to stay away from the bee’s nest you boys stirred up when you came ashore.”

“Um,” Charlie said, clearing his throat.

Jane squinted at him. “Ha. I should have known. You’re a real cowboy, aren’t you?” She shook her head. “Don’t matter much anyways. The disease would have snuck aboard either way.”

Charlie shifted his gaze to Liebold and Bryant. “I don’t know if Doc is up to this.”

Which was also crew business, but he needed Jane’s help.

She held up her mug as Isko came around with a fresh pot of coffee. “Me and the girls will be happy to pitch in and make ourselves useful, if that’s what you want.”

“We’d be grateful. What do you recommend we do to stop it from spreading?”

“I know water is an issue and all, but everybody really needs to wash their hands as often as possible. Especially the cooks.”

Charlie nodded. “We’re tight on water, but we’ll make it work.”

“The main thing is to keep an eye out for anybody who gets symptoms, isolate them, and treat them as best we can.”

“Where the hell are we supposed to do that?” Bryant said. “We can barely fit everybody aboard. We don’t have any spare rooms.”

“I have no idea,” Jane said. Then she sipped her coffee and leaned back in her chair with another contented sigh.

“We’ll have to take our meals in our rooms,” Charlie said. “Turn the wardroom into a sick ward. We’ve got at least two sick people, the captain and whoever brought the disease aboard. I saw somebody else coughing. There are probably even more now. We’ll need to screen everybody for symptoms and get them here quick.”

The men nodded. Charlie wiped sweat from his forehead. He’d shared a room with the captain for hours. The Navy labeled it a stateroom, but it was about the size of a large closet. Did he catch the germ? And if he did, how long did he have?

God, they were already down two line officers.

Then it truly hit him. He was in command again. And this time, he had no safety cushion. If Charlie went to Hunter with a problem now, the only thing he’d get out of the captain would be more incoherent shouting.

“How long until the captain recovers?” he asked Jane.

“Days. A week. Who knows?”

“All right. From here on out, we’re going to focus on getting to Darwin. Bryant, can you handle both engineering and exec responsibilities?”

The man grinned. “You bet, boss.”

“Jack, you’ll take over plotting and communications.”

“Aye, Charlie.”

“And Jane?”

She looked up from her mug. “Ye

ah?”

“Screen every single human being on this boat, and send them here if they’re sick. Lieutenant Liebold will have the chief of the boat come along to make sure everybody complies. Though, I doubt the men will have a problem with you taking a look at them.”

Jane smirked. “Aye, aye.”

The men started as the klaxon wailed. Ensign Miller, who was officer of the deck, was diving the boat. Charlie glanced at his watch. Too early. They still had four hours of darkness left. Something was up.

The 1MC buzzed. Miller’s voice: “Captain to Control.”

Bryant ground out his cigarette in the ashtray. “That would be you, hotshot.”

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR

SOME OPPORTUNITIES

Charlie hustled into the control room. “What have you got?”

“We found another Jap battle group!” The young ensign looked past Charlie’s shoulder, expecting to see the captain appear.

“Make your report, Miller.”

The ensign stiffened at Charlie’s formality. “Radar reported contacts, Mr. Harrison. North by northwest. Bearing, one-seven-five. Range, 10,000 yards. After we dived, Sound picked up multiple sets of heavy and light screws.”

“What’s their speed?”

“Twenty-five knots.”

That meant warships; merchants traveled at less than half that speed.

“Up scope.” Charlie wrapped his arm around the periscope as it rose. “How does she head?”

“Two-double-oh.”

Charlie scanned the darkness for the enemy. Moonlight glowed on the whitecaps. He couldn’t see them in the dark. They were too far away, no threat. He could easily avoid them. J.R. Kane had taught him a captain had to pick his battles.

Fighting a battle group was David and Goliath even in the best of circumstances. But this time, David would fight with one hand tied behind his back. Sabertooth was leaking and carrying civilians. She had an infectious disease aboard. She was missing her most experienced officers.

Best to let Goliath and his band of Philistines go on their merry way.

Our War

Our War The Children of Red Peak

The Children of Red Peak Hara-Kiri_a novel of the Pacific War

Hara-Kiri_a novel of the Pacific War The Killing Floor

The Killing Floor The Infection

The Infection The Infection ti-1

The Infection ti-1 Silent Running: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 2)

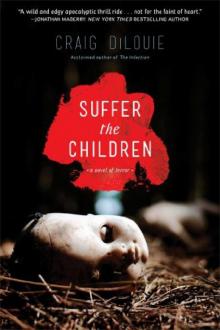

Silent Running: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 2) Suffer the Children

Suffer the Children Crash Dive: a novel of the Pacific War

Crash Dive: a novel of the Pacific War Pandemic r-1

Pandemic r-1 Over the Hill: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 6)

Over the Hill: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 6) Battle Stations: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 3)

Battle Stations: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 3) This Is the End: The Post-Apocalyptic Box Set (7 Book Collection)

This Is the End: The Post-Apocalyptic Box Set (7 Book Collection) Hara-Kiri

Hara-Kiri Hara-Kiri: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 5)

Hara-Kiri: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 5) Contact!: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 4)

Contact!: a novel of the Pacific War (Crash Dive Book 4) Tooth And Nail

Tooth And Nail One of Us

One of Us